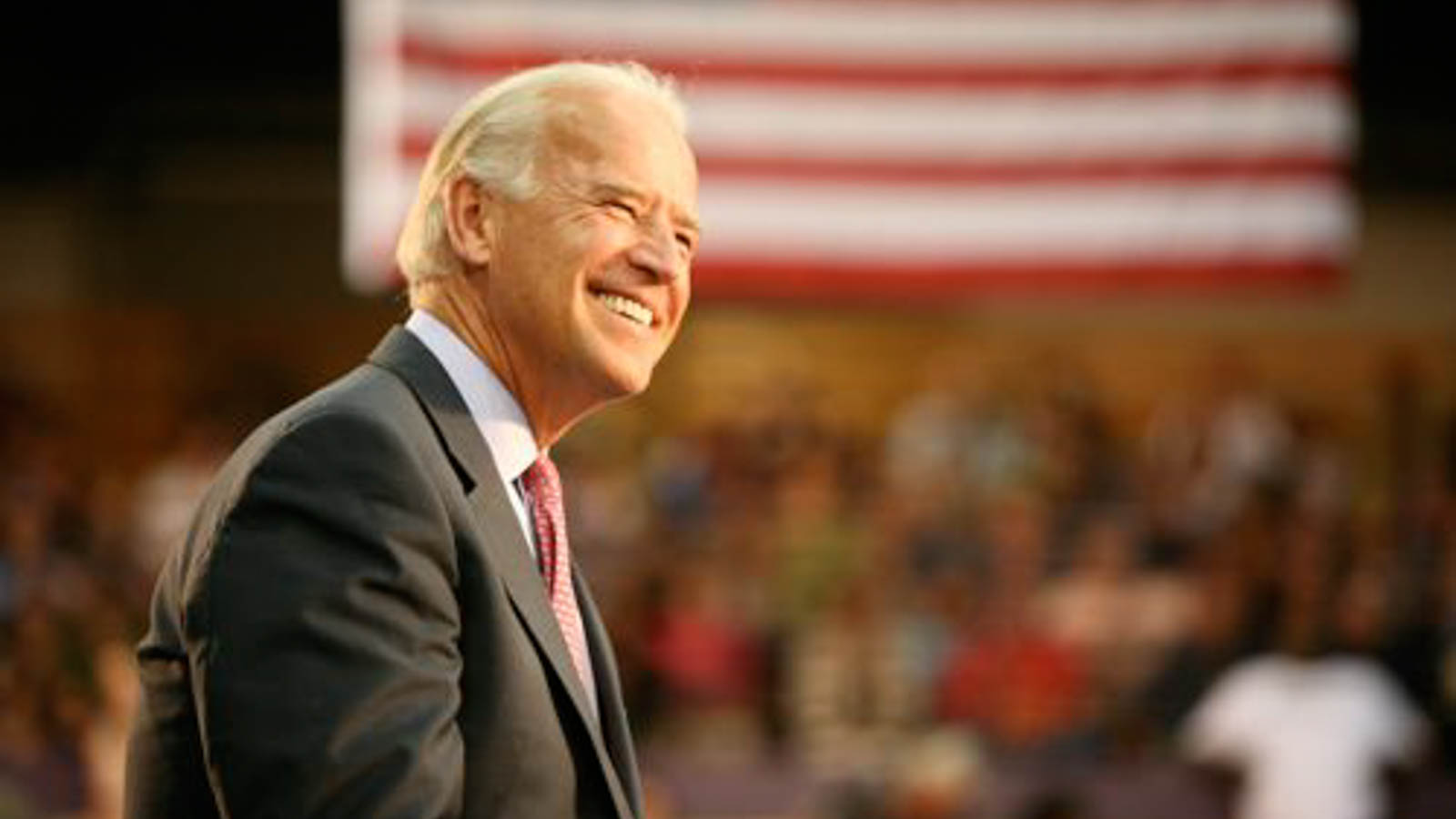

Former Vice President Joe Biden is making another run for the White House, he announced April 25, 2019.

The former Delaware senator, who served as chair of the influential Judiciary Committee that helped shape U.S. drug policy during an era of heightened scaremongering and criminalization, was among the most prominent Democratic drug warriors in Congress for decades.

And while many 2020 Democratic candidates have evolved significantly on drug policy — and particularly marijuana reform — over the years, Biden has barely budged. While he’s recognized the long-term harms of certain pieces of legislation he supported and has made some efforts to attempt to repair that damage, overall he’s maintained a firm opposition to cannabis legalization — a stance that sets him far apart from every other major Democratic contender.

Biden served as vice president under President Barack Obama, and he’s expressed pride that he was entrusted to oversee matters of criminal justice from the White House. To the administration’s credit, the Obama Justice Department was responsible for enacting a few major drug policy changes—especially, the Cole memorandum, which cleared the way for state-legal marijuana businesses to operate largely without federal interference. But it was also during Obama’s time in office that the department declined to put different cannabis laws on the books, rejecting petitions to reschedule the plant under the Federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA).

Where Joe Biden stands on cannabis and drug policy:

Legislation And Policy Actions

The 1980s were a time of extraordinary upheaval for U.S. drug policy, with lawmakers pushing numerous bills meant to scare people away from using controlled substances by way of propaganda and threats of incarceration. Biden was among the loudest voices backing anti-drug measures. While there has been a shift in tone over the years, his track record will likely be a point of contention on the campaign trail.

Biden introduced the Comprehensive Narcotics Control Act of 1986. The wide-ranging anti-drug legislation called for the establishment of a cabinet position to develop the federal government’s drug enforcement policies — a role that fits the description of the “drug czar” position, a term the senator coined in 1982 and which was subsequently created to lead the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

“We need one person to call the shots,” Biden said at the time, while also criticizing the Reagan administration’s anti-drug efforts, saying “their commitment is minuscule in terms of dollars.”

The bill would have also expanded Justice Department authority to seize assets in drug cases, impose mandatory minimum sentences for offenses involving certain amounts of controlled substances, increase other drug penalties and add new substances to the CSA. It also authorized appropriations for the U.S. Department of Defense for “enhanced drug enforcement assistance” — an early indication of what would become an increasingly militarized drug war — and asked the military to “prepare a list of defense facilities which can be used as detention facilities for felons.”

Further, the legislation would have required the Secretary of the Interior to create a program to eradicate marijuana on Indian territory. It also included a provision for Congress to urge the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs to create a new international convention “against illicit traffic in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances,” and called for “more effective implementation of existing conventions relating to narcotics.” It also proposed setting aside money for the development of “herbicides for use in aerial eradication of coca,” which would later become a key part of the controversial Plan Colombia program.

In 1989, Biden filed a bill that would have required the U.S. to propose a program to the United Nations in which member states could have their debts partially forgiven in exchange for committing to use resources to reduce international drug trafficking. One example of something a country could do to reap those rewards would be to “increase seizures” of substances including marijuana.

Another expansive anti-drug bill the senator introduced was called the Federal Crime Control Act of 1989. Among other things, the legislation would have expanded asset forfeiture authorities, required individuals charged for certain drug crimes to be held for sentencing or appeal rather than released on bail and mandated that the attorney general “aggressively use criminal, civil, and other equitable remedies … against drug offenders.”

It proposed authorizing the president to declare that a state or part of a state is a “drug disaster area,” which would be entitled to grants of up to $50 million “for any single drug-related emergency.”

Under the legislation, the Justice Department would establish a new division dedicated to maintaining or increasing “the level of enforcement activities with respect to criminal racketeering, narcotics trafficking, money laundering, asset forfeiture, international crime, and civil enforcement.” It would be directed to “establish at least 20 field offices of the Division to be known as Organized Crime and Dangerous Drug Strike Forces” and “at least ten International Drug Enforcement Teams.”

Biden also introduced the National Drug Control Strategy Act in 1990. It included a number of jarring provisions meant to deter drug use, including the establishment of “military-style boot camp prisons” that could be used as alternative sentencing options for people convicted of drug-related offenses who tested positive for a controlled substance at the time of an arrest or following an arrest.

The legislation also called for a requirement that people pass a drug test as a condition of probation or parole before a sentence is imposed, and also subsequently submit to at least two drug tests. It would also require federal employees working in a division that deals with children to pass a background check, specifying that any controlled-substances conviction on a person’s record is barred from employment.

Then there’s the propaganda provision of the bill, under which the director of the ONDCP would be required to “provide resources to assist members of the motion picture and television industries in the production of programs that carry anti-drug messages.”

The bill would also have authorized appropriations under the Arms Export Control Act and the Foreign Assistance Act to be used to train and assist military and law enforcement in their anti-drug production and trafficking operations. A separate provision would have encouraged the Central Intelligence Agency to enhance human intelligence that could be used to combat international drug trafficking.

Biden introduced a bill on capital punishment in 1990 that was later amended to include a provision known as the Drug Kingpin Death Penalty Act, which called for the imposition of capital punishment for anyone who killed someone while carrying out a federal drug offenses and was the head of a criminal enterprise who qualified for mandatory life imprisonment.

In 1991, Joe Biden boasted of expanding the death penalty for major drug dealers and widening asset forfeiture, as well as restricting judges’ discretion in sentencing. “The government can take everything you own, from your car to your house to your bank account!” pic.twitter.com/juKJhEQ8Ep

— Zaid Jilani (@ZaidJilani) April 3, 2019

“There is now a death penalty,” he said later, in a 1991 floor speech. “If you are a major drug dealer, involved in the trafficking of drugs, and murder results in your activities, you go to death.”

The proposal also increased penalties for certain drug offenses committed near schools or colleges and directed the attorney general to “develop a model program of strategies and tactics for establishing and maintaining drug-free school zones.” It declared that drug offenses committed by juveniles would be treated “as offenses warranting adult prosecution,” set aside funds to create a national drug and related crime tip hotline and authorized “payment of awards for information or assistance leading to a civil or criminal forfeiture.”

The Senate passed that amended legislation, and Biden was among those who voted in favor of it.

The Biden-Thurmond Violent Crime Control Act of 1991, which the senator sponsored alongside Republican Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, proposed prohibiting people with “serious drug misdemeanor” convictions from purchasing firearms and creating a mandatory five-year penalty for firearms possession by “serious drug offenders.”

An amended version of the bill, which Biden voted in favor of, also made federal marijuana laws more punitive by reducing “from 100 to 50 the number of marihuana plants needed to qualify for specified penalties” and stipulated that people convicted of three felony drug charges should be handed a sentence of life imprisonment without release.

Additionally, the bill would have increased penalties for the use of a controlled substance in public housing, expanded the definition of “drug paraphernalia” under the CSA to include things like scales and syringes and prohibited the advertisement of Schedule I drugs such as cannabis.

In 1993, Biden filed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, a bill that would have required the director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts to establish a drug testing program for federal offenders on “post-conviction release.” It also would’ve increased penalties for those convicted of drug distribution in “drug-free” zones and ban advertising “which aims to illegally solicit or sell drugs.”

It would also direct state and federal court clerks to “report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and prosecutors the name and taxpayer identification number of anyone accused of a drug, money laundering, or racketeering crime who posts cash bail exceeding $10,000.”

The following year he filed separate legislation of the same name. While that version was indefinitely postponed in the Senate, the House companion bill — the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, also known colloquially as the crime bill — passed both chambers and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton in September 1994. Biden voted in favor of the legislation, which has since become known as one of the largest drivers of mass incarceration in the U.S.

Among other things, the wide-ranging anti-crime bill established the aforementioned federal drug testing program for prisoners on release, amended the federal code to make certain drug-related murders punishable by death, enhanced penalties for drug dealing in “drug free” zones, allowed the president to declare “drug emergency” areas and to “take action to alleviate the emergency” and required courts to submit information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation about juveniles who are convicted of certain drug crimes.

Biden used the expansion of the death penalty to defend the crime bill he helped write against critiques that it was too soft. He emphasized in a 1994 floor speech that the legislation included “60 new death penalties — brand new.”

Delaware Senator Joe Biden on the floor in 1994, defending his crime bill against the charge that it wasn’t tough enough. “There are 60 new penalties, 60 new death penalties! Brand new! 60!” pic.twitter.com/mtUQ3B74P7

— Zaid Jilani (@ZaidJilani) April 4, 2019

Biden sponsored a bill in 1997 to establish the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas Program within the ONDCP.

The senator, who went to great lengths to be regarded as friendly to law enforcement, also introduced a resolution in 2008 “honoring the men and women of the Drug Enforcement Administration” on the department’s 35th anniversary, specifically cheering the agency’s record of “aggressively targeting organizations involved in the growing, manufacturing, and distribution of such substances as marijuana.”

“The Senate … gives heartfelt thanks to all the men and women of the DEA for their past and continued efforts to defend the people of the United States from the scourge of illegal drugs and terrorism,” the resolution states.

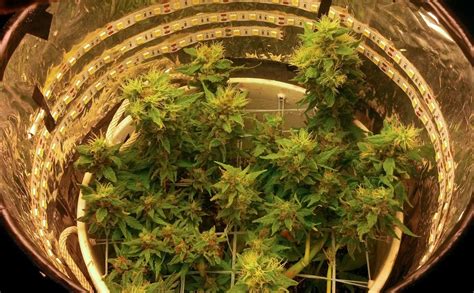

In 2003, Biden sponsored a bill to amend the CSA to “prohibit knowingly leasing, renting, or using, or intentionally profiting from, any place … whether permanently or temporarily, for the purpose of manufacturing, storing, distributing, or using a controlled substance.” The Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act, which later became the Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy (RAVE) Act, has been blamed for making festivals and music events where drugs such as MDMA, or ecstasy, are taken to ironically be less safe by discouraging operators from providing on-site harm reduction services out of fear they’d be prosecuted for knowingly allowing drug use. He co-sponsored a later version as well.

Biden also cosponsored a number of controversial anti-drug bills filed by other lawmakers during his time in the Senate.

He signed on as the lead Democratic co-sponsor of Thurmond’s Criminal Code Reform Act in 1981. The bill would have increased penalties for trafficking in drugs including “large amounts” of marijuana. The next year, Biden also appeared as the lead Democratic co-sponsor of Thurmond’s Violent Crime and Drug Enforcement Improvements Act, which would have expanded federal asset forfeiture authorities, made it so juveniles can be transferred to adult court for certain violent or drug-related crimes and established a new office to “plan and coordinate drug enforcement efforts” for the federal government.

Another Thurmond bill that Biden signed on to in 1983 proposed expanding federal asset forfeiture authorities.

In 1998, as states began making moves to allow medical cannabis, the senator co-sponsored a resolution “in support of the existing Federal legal process for determining the safety and efficacy of drugs, including marijuana and other Schedule I drugs, for medicinal use.”

“Congress continues to support the existing Federal legal process for determining the safety and efficacy of drugs and opposes efforts to circumvent this process by legalizing marijuana, and other Schedule I drugs, for medicinal use without valid scientific evidence and the approval of the Food and Drug Administration,” the resolution stated. It also expressed concerns about “ambiguous cultural messages about marijuana use are contributing to a growing acceptance of marijuana use among children and teenagers” and voiced support for federal authorities enforcing prohibition “through seizure and other civil action, as well as through criminal penalties”

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, chief sponsor of the resolution, described it this way: “Our resolution addresses the effort by the drug legalization lobby in this country to get marijuana and other dangerous drugs on the streets, in our homes, and in our schools. These groups have been trying to do this for years. Sadly, they have been somewhat successful.”

Biden was an original co-sponsor of another infamous drug-related bill, the Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1986. The House version, which he voted in favor of, was ultimately signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. It’s best known for creating sentencing disparities for crack versus powder cocaine; it imposed a 1-to-100 crack to powder cocaine ratio, whereby one gram of crack was equivalent to 100 grams of powder cocaine under the law. The provision led to significant racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

The bill also laid out various penalties for marijuana and other drugs, and it established “a program for the eradication of marijuana cultivation within Indian country.”

About 20 years later, Biden sponsored a bill attempting to make up for the crack-powder cocaine disparity by increasing the amount of cocaine that qualified an individual for a mandatory minimum sentence and also eliminating the five-year mandatory minimum for first-time possession of crack cocaine. The sentencing disparity was eventually lessened when Congress passed a bill in 2010 lowering the weight ratio from 100:1 to 18:1 for crack versus powder cocaine. The legislation was signed while Biden served as vice president.

The senator also voted in favor of Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which formally established ONDCP, made first-time possession of crack subject to a five-year mandatory minimum sentence and also included provisions to increase drug treatment and prevention efforts. Biden noted that the bill, which became law, “contains many provisions that we have sponsored in the past.”

Biden voted in favor of a massive omnibus bill in 1999 that included language directing the drug czar to “take such actions as necessary to oppose any attempt to legalize the use of a substance” in Schedule I.

It also expressed the sense of Congress that “the several States, and the citizens of such States, should reject the legalization of drugs through legislation, ballot proposition, constitutional amendment, or any other means” and made clear its opposition to “efforts to legalize marijuana for medicinal use without valid scientific evidence and the approval of the Food and Drug Administration.”

Curiously, Biden once made an earmark request for almost half a million dollars to go toward the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE), the youth anti-drug campaign that rose to popularity in the 1980s and ’90s. Harper’s pointed out that the main lobbyist for DARE previously worked under Biden while he was Judiciary Committee chairman and also contributed $2,300 to the senator prior to the request.

Quotes And Social Media Posts

There are no mentions of marijuana on Biden’s social media feeds. But that doesn’t mean he hasn’t been talking about the issue. Unlike other candidates for the Democratic nomination, however, the quotes one finds when searching through his past are not supportive of reform. For the most part, they’re the exact opposite.

In a 1974 article from the Washingtonian, the senator — at that point 31 years old, making him the youngest member of the Senate — tried to distance himself from being identified as liberal. While he argued he was progressive on “civil rights and civil liberties,” he said, “when it comes to issues like abortion, amnesty, and acid, I’m about as liberal as your grandmother.”

“I don’t think marijuana should be legalized,” he said.

About 3 1/2 decades later, in 2010, the then-vice president said, “I still believe it’s a gateway drug. I’ve spent a lot of my life as chairman of the Judiciary Committee dealing with this. I think it would be a mistake to legalize.”

“The punishment should fit the crime,” he said. “But I think legalization is a mistake.”

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush addressed the nation in a televised appearance to outline the administration’s drug control strategy. But even his proposals did not satisfy Biden’s thirst for a tougher and more punitive approach. He delivered the Democratic response to that address.

“Every president for the past two decades — Democrat and Republican alike — has declared war on drugs — and each of them has lost that war and lost it miserably,” Biden said. “They lost because they attempted to deal with only part of the drug problem. They lost because their initiatives were pulled apart by bureaucratic squabbling among their advisors. They lost because they always did too little and they did it too late.

“The trouble is that the president’s proposals are not big enough to deal with the problem. His rhetoric isn’t matched by the resources we need to get the job done. Quite frankly, the president’s plan is not tough enough, bold enough or imaginative enough to meet the crisis at hand.”

Throughout his own time in the White House as vice president, Biden consistently took an opposing stance on marijuana reform proposals. He said in 2012 that he had “serious doubts that decriminalization would have a major impact on the earnings of violent criminal organizations, given that these organizations have diversified into criminal activities beyond drug trafficking,” for example.

During a trip to Mexico, Biden discouraged Latin American countries from legalizing marijuana, arguing that while he understood their interest in pursuing alternative approaches to curb prohibition-related violence, the pros of legalization were outweighed by the cons.

“I think it warrants a discussion. It is totally legitimate,” he said. “And the reason it warrants a discussion is, on examination you realize there are more problems with legalization than with non-legalization.”

He was asked in 2014 whether he supports legalization and flatly said “no,” but added that “the idea of focusing significant resources on interdicting or convicting people for smoking marijuana is a waste of our resources” and that he “support[s] the President’s policy” of non-intervention in state laws via the Cole memo.

“Our policy for our administration is still not legalization, and that is and continues to be our policy,” Biden said.

“But on the entire criminal-justice front, the good news is there are two things the President asked in the beginning that I wanted to have sort of day-to-day jurisdiction over. And one was I said the violence-against-women portfolio and law enforcement, cops,” he said in the same interview with TIME Magazine, touting his role in shaping the administration’s policies. “When we put together the budget, I’ve been basically the guy who has the final say in the criminal-justice side of the budget. So and I’m still a point person along with the Attorney General with law enforcement, with the criminal justice system and all those issues relating to violence against women.”

“So on the criminal-justice side, I am not only the guy who did the crime bill and the drug czar, but I’m also the guy who spent years when I was chairman of the Judiciary Committee and chairman of [the Senate Foreign Relations Committee], trying to change drug policy relative to cocaine, for example, crack and powder. I mean, I worked for the last five years I was there, and [Illinois Sen. Richard] Durbin’s continuing to work. And [New York Sen. Chuck] Schumer. And the President shares this. And I’m still engaged in those things… In the meantime, there were some things that came, everything from marijuana to drug control. And I was on another assignment. When I’m in there, when we’re both in town, I attend every meeting [Obama] has.”

Biden has spent a lot of time talking about the importance of the drug czar position, an idea he championed into creation. And William Bennett, the first person to serve in that role and one of the “architects” of the drug war, shared an anecdote in 2018 about how Biden viewed his performance. According to Bennett, Biden said “you’re not being tough enough” to the man who once said he wasn’t bothered by the idea of publicly beheading drug dealers.

As a senator in 1999, Biden strongly supported an interventionist initiative aimed at disrupting drug cartels and a political insurgent group in Colombia. Part of that plan involved spraying aerial herbicide on coca plants, which led to health problems for those on the ground as well as environmental damage. While he faced criticism at the time, he maintained his belief that the intervention was a success in a 2015 editorial in The New York Times.

“In 1999, we initiated Plan Colombia to combat drug trafficking, grinding poverty and institutional corruption — combined with a vicious insurgency — that threatened to turn Colombia into a failed state,” the then-vice president wrote. “Fifteen years later, Colombia is a nation transformed.”

In 2007, Biden defended his vote in favor of additional border wall fencing by peddling a myth that has since been echoed repeatedly by President Donald Trump, telling CNN’s Wolf Blitzer that he “voted for the fence related to drugs.”

“A fence will stop 20 kilos of cocaine coming through that fence. It will not stop someone climbing over it or around it,” Biden said, despite the fact that the vast majority of drug smuggling occurs at legal ports of entry. “And it is designed not just to deal with illegals, it’s designed with a serious drug trafficking problem we have.”

Asked in 2016 whether he regretted promoting the 1994 crime legislation, Biden said: “not at all.”

“When you take a look at the crime bill, of the money in the crime bill, the vast majority went to reducing sentences, diverting people from going to jail for drug offenses into — what I came up with it — drug courts, providing for boot camps instead of sending people to prison so you didn’t relearn whatever the bad thing that got you there in the first place,” he said. “We had enormous success.”

“There are things that I would change,” he said, citing a carjacking provision he said the administration wanted to include. “But by and large, what it really did, it restored American cities.”

But by January 2019, as Biden was gearing up for a presidential run, he seemed less bullish about defending his role in shaping the criminal justice world that emerged out of the 1990s.

“I haven’t always been right,” he said. “I know we haven’t always gotten things right, but I’ve always tried.”

He added that sentencing disparities for crack and cocaine “trapped an entire generation” and added that the legislation “was a big mistake when it was made.”

About a decade after Biden helped write into law some of the country’s most consequential anti-drug laws, he did eventually speak out against sentencing disparities for crack vs. powder cocaine, and he also recognized his role in shaping the criminal justice system to doled out those sentences.

“I might say at the outset in full disclosure, I am the guy that drafted this legislation years ago with a guy named Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was the senator from New York at the time,” Biden said at a Senate hearing in 2008. “And crack was new.”

“It was a new ‘epidemic’ that we were facing. And we had at that time extensive medical testimony talking about the particularly addictive nature of crack versus powder cocaine. And the school of thought was that we had to do everything we could to dissuade the use of crack cocaine. And so I am part of the problem that I have been trying to solve since then, because I think the disparity is way out of line.”

Biden has also characterized the “three strikes system,” whereby people would be sentenced to life after being convicted of three violent felonies, as “simplistic” and argued against it.

“I think we’ve had all the mandatory minimums that we need,” Biden said in 1993. “We don’t need the ones that we have.”

When Biden was in the Senate, he reportedly told staffers that he wanted people to think of him any time they heard the words “drugs” and “crime.” He has his team “think up excuses for new hearings on drugs and crime every week — any connection, no matter how remote.”

But in the modern political climate, where voters are increasingly supportive of policies to reform the harsh drug laws that Biden pushed, that kind of word association isn’t likely to win him much favor, especially among Democrats.

Most recently, in April 2019, Biden appeared on a panel dedicated to the opioid epidemic. During that panel, a professor claimed that pain patients who consume cannabis experience the same levels of pain and don’t reduce their intake of opioid painkillers, and she criticized state moves to allow medical marijuana. Biden applauded the talk and also seemed to whisper “she’s right” to the guest beside him.

He also said that “a little pain is not bad” at one point during the panel. Taken together, it seems Biden hasn’t evolved much since 2007, when he was running for president and also complained about “pain management and chronic pain management” in the U.S. and said there has “got to be a better answer than marijuana.”

“There’s got to be a better answer than that,” he said at the time, allowing that he would at least seek to stop federal raids on state-legal medical cannabis patients and providers. “There’s got to be a better way for a humane society to figure out how to deal with that problem.”

Biden’s 2020 campaign website doesn’t list support of any specific cannabis reform measures but instead says the country needs to “reform the criminal justice system to prioritize prevention, eliminate racial disparities that don’t fit the crime, and help make sure formerly incarcerated individuals who have served their sentences are able to fully participate in our democracy and economy.”

Personal Experience With Marijuana

At the same time that Biden has been one of the most vociferous defenders of harsh, anti-drug policies, he has also seen people close to him impacted by drug criminalization. His daughter Ashley was arrested for marijuana possession and allegedly used cocaine in a video that a “friend” of hers attempted to sell for $2 million. And his son Hunter was kicked out of the military after testing positive for cocaine during a random drug test.

It does not appear that Biden has publicly commented on any personal experience he has had with marijuana or other drugs.

Marijuana Under a Biden Presidency

It will be interesting to see how Biden addresses questions about marijuana and drug policy in general when put on stage alongside a crowd of other candidates that uniformly supports legalization. Will he double down in his opposition or make vague promises not to crack down on legal cannabis states? Could he be pushed even further — to a point where he comes out in support of modest marijuana reform legislation such as allowing banks to service state-legal cannabis businesses? Or will he endorse legalization outright in an effort to take the issue off the table?

For now, a review of Biden’s record signals that he would not likely be a champion for marijuana reform if elected president.

This article was republished from Marijuana Moment under a content syndication agreement. Read the original article here.

Featured Image: “Joe Biden, September 3, 2008” by Barack Obama is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0