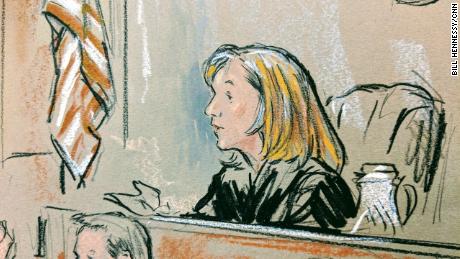

But the hearing lasted more than 90 minutes. It took that long because Judge Amy Berman Jackson always comes prepared.

On that day, Jackson spoke uninterrupted to the parties for almost an hour — 43 typed pages in total of a transcript released later. She told Manafort and the special counsel’s office that she decided he had intentionally lied during his cooperation interviews and grand jury testimony following a guilty plea.

The decision propelled Manafort’s court case into its final stage, with the conclusion set for Wednesday morning, the final sentencing hearing for Donald Trump’s former campaign chairman. As she’s done several times before, Jackson will have the opportunity to revisit every twist and turn of Manafort’s 17 months facing federal charges and give her assessment of what’s right, wrong and just.

On Thursday, Jackson will continue her work on special counsel-related cases, with another hearing for former Trump adviser Roger Stone.

Jackson’s approach to deftly summarize the events and the law before her, with exhaustive preparedness, has become her hallmark, even as the various Mueller cases before her have become more complicated, unpredictable and dramatic.

“She’s an extremely competent woman. She’s very focused,” her longtime friend Maureen Asterbadi said. Asterbadi and Jackson met two decades ago when their sons attended the same grade school, and have stayed in touch.

They don’t talk much about Jackson’s time on the bench or about politics at all, Asterbadi said, yet Jackson’s deliberate approach comes across in everything in which she’s involved. The judge is an accomplished singer and even performs in a local theater group, Asterbadi said, and has a close friend group of women outside the legal profession, including many who recommended her to the Senate Judiciary Committee during her confirmation process.

As a friend, “she’s the least judgmental person I know. And the fairest person I know,” Asterbadi said.

Crossed paths with other Manafort judge during corruption trial

Jackson’s accolades in Washington date back to long before she took the federal bench in 2011 as a nominee of President Barack Obama.

With double Harvard degrees, she graduated in the same undergraduate and law classes as Chief Justice John Roberts.

A stint as a prosecutor after law school led Jackson to practice trial law for much of her career. For about a decade before she became a judge, Jackson represented criminal defendants and others in litigation at a well-known Washington trial firm, Trout Cacheris & Solomon.

Coincidentally, that work placed her opposite other major players who’ve now worked on the Manafort proceedings.

When Jackson’s then-law firm took on a client in the Enron corporate prosecution, Jackson and her colleagues negotiated opposite prosecutor Andrew Weissmann, who has led the prosecution against Manafort in DC.

And, in one of her most significant trials, Jackson defended former US Rep. William Jefferson in his corruption trial before Judge T.S. Ellis.

Ellis sentenced Manafort last week to 47 months in prison for financial fraud convictions, far below the recommended sentence he faced and the public’s expectations. Outraged lawyers criticized the sentence as unfair and racially biased, with many comparing Ellis’ Manafort decision to the 13 years he gave Jefferson, a black Democrat. (Jefferson ultimately served five years in prison for the corruption, after appeals court decisions led to his early release.)

At the Jefferson trial, according to court transcripts, Jefferson’s defense team clashed with Ellis in much the same way the judge did with Mueller’s team of prosecutors.

Despite the history, Jackson will weigh Manafort’s criminal counts and admitted crimes separately from Ellis on Wednesday. She cannot sentence the former Trump campaign chairman to more than 10 years in prison under the law. He has pleaded to only two crimes, conspiracy and witness tampering, yet admitted in her court to several others, including money laundering and illegal foreign lobbying in the US for Ukrainian politicians.

Manafort’s collection of crimes and plea agreement place his recommended sentence at about double the 10-year max—meaning Jackson may lean toward the high end of possible sentences. It is not yet known whether she will add her sentence for Manafort onto Ellis’, or whether she will decide he should serve them concurrently.

Using bench as a pulpit

In her eight years as a judge, Jackson has several times used her pulpit as a way to send a message about ethics in politics.

When another Mueller defendant, Alex Van Der Zwaan, came before Jackson at his sentencing for lying to investigators last year, she did not shy away from giving him prison time. His sentence, of 30 days, was harsher than the two weeks George Papadopoulos got from her colleague Judge Randy Moss for the same crime in Mueller’s investigation.

At another high-profile sentencing, Jackson gave former Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. two-and-a-half years in prison for fraud and conspiracy. She also took the opportunity to discuss the burden of those working at the top of the country’s political class.

“As a public official, you’re supposed to live up to a higher standard of ethics and integrity, and that’s not unfair. You chose that role for yourself. After holding yourself out year after year and asking the public to name you to a position of awesome power and leadership and responsibility, to trust you, you are a symbol,” she told Jackson (no relation) at his sentencing. “You owe them, at the very least, scrupulous adherence to federal law.”

Of course, not all politicized cases that Jackson has handed have drawn out her commentary. For instance, she dismissed a wrongful death case against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton related to a terrorist attack on State Department personnel in Benghazi, Libya, in 2012. In that lawsuit’s final opinion, Jackson made note that “nothing about this decision should be construed” as commentary on Clinton’s statements after the attack or about her use of a private email server, which families of the victims said exposed the Americans to the attack.

At the Van der Zwaan sentencing, Jackson condemned the Dutch lawyer — who came from a privileged background — for not expressing much remorse, and for knowing better than to commit the crime he did.

“While it’s true that he did plead guilty and while it would not be fair to treat this defendant more harshly because it’s a high-profile investigation, I have come to the conclusion that the offense warrants a period of some incarceration,” Jackson said.

Revoked Manafort’s bail

Manafort may face even more of a critique, given the number of times he’s crossed the court since his indictment. Manafort broke a gag order Jackson placed on his case by ghost writing an op-ed for a Ukrainian newspaper after his arrest. He also attempted to reach out to potential witnesses in his case to sway their recollections about his foreign lobbying work.

She revoked Manafort’s bail and sent him to jail last June following prosecutors’ announcement of the witness tampering allegation.

Jackson hasn’t yet summarized Manafort’s actions in full, taken on the whole — though she may on Wednesday when speaking to him about the time he will serve. Manafort will also have the opportunity to address her in court. At his proceeding last week, he expressed regret for the situation he was in but no remorse for his crimes.

“I am concerned that you seem inclined to treat these proceedings as just another marketing exercise and not a criminal case brought by a duly appointed federal prosecutor in a federal court,” she told Manafort last year.

She will eventually sentence Manafort’s co-conspirator Rick Gates as well, who’s become a key, long-term cooperator of Mueller’s. Other Mueller defendants whose cases have landed with her, including 12 alleged Russian hackers and Manafort’s associate Konstantin Kilimnik, haven’t yet appeared in her courtroom to enter pleas.

Roger Stone

On Thursday, Stone appears once again in Jackson’s courtroom.

Stone drew out Jackson’s trial-lawyer side during a recent proceeding. At that hearing, Jackson jumped in while the defense attorney and prosecutor questioned Stone in the witness box. She asked him about details of how and why he shared a photo on Instagram with crosshairs behind her head.

At first, he said he selected the image from among a few, then under her questioning said he randomly chose it. “Randomly does not involve the application of human intelligence,” Jackson shot back.

Stone apologized repeatedly for the post. Still, Jackson ordered him not to speak any more about the case. Even while the online post threatened her directly, she explained the law behind how she arrived at restricting his speech.

“Order and decorum and dignity are not just old-fashioned pleasantries,” Jackson told Stone, “they’re fundamental to the fair administration of justice, which inures to the benefit of everyone, including the defendant. And it’s my responsibility to uphold that order.”

Views: 560