“Blunt Truths” tells the origin story of marijuana prohibition.

The story so far: Racism lies at the heart of America’s marijuana prohibition. For the first three years of Harry Anslinger’s tenure as commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), he viewed marijuana as a local problem limited to the southwestern United States. But, when he feared that marijuana was spreading into “white culture,” he made marijuana prohibition his priority. Lacking a constitutional basis to prohibit marijuana use, Anslinger had to find another way. He did.

On August 2, 1937, Harry Anslinger got his way: President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 into law.

FDR’s signature on Anslinger’s legislation (Anslinger wrote the Tax Act himself) made fact out of all the fictions Anslinger had used to get marijuana prohibition up onto its feet and then up into the air. It was as if all of Anslinger’s gore files, his collection of newspaper clippings and scribbled notes that painted marijuana as “The Assassin Of Youth,” had magically been made real — especially the most outrageous.

Marijuana’s problem was that no one stood up in marijuana’s defense. No one knew they had to. Or should.

Anslinger’s congressional allies moved stealthily. Rep. Robert L. Doughton, a Republican from North Carolina, introduced HR 6835 and led it through a committee hearing where only one person was given the chance to speak on marijuana’s behalf, Dr. William C. Woodward of the American Medical Association, which was routinely consulted on medical legislation.

Woodward reluctantly was allowed to testify, according to the non-profit group, Doctors for Cannabis Regulation, and told Congress, “There is nothing in the medicinal use of Cannabis that has any relation to Cannabis addiction. I use the word ‘Cannabis’ in preference to the word ‘marihuana,’ because Cannabis is the correct term for describing the plant and its products.… In other words, marihuana is not the correct term.”

In “Cannabis, A History,” Martin Booth wrote that although Woodward agreed that marijuana should be regulated, he vehemently disagreed with almost everything else the Tax Act and Anslinger were saying about marijuana and, more importantly, he disagreed with what they were trying to accomplish.

The Act passed almost as an afterthought. “The debate lasted a matter of minutes, the Speaker – long-standing Texas Democrat Sam Rayburn, seemed unsure what the bill was about and no vote was taken,” according to Booth. Instead, a “teller system” counted whoever was still there on a late Friday afternoon, and, it assumed they all were “for” the act’s passage.

Just like that, after the Senate agreed a few weeks later, it was law.

Marijuana was still technically legal. But, if you bought or sold marijuana, you had to pay $1 for a government stamp to finalize the transaction. Unfortunately, the stamp itself was unavailable. Anyone possessing marijuana, therefore, was breaking the law.

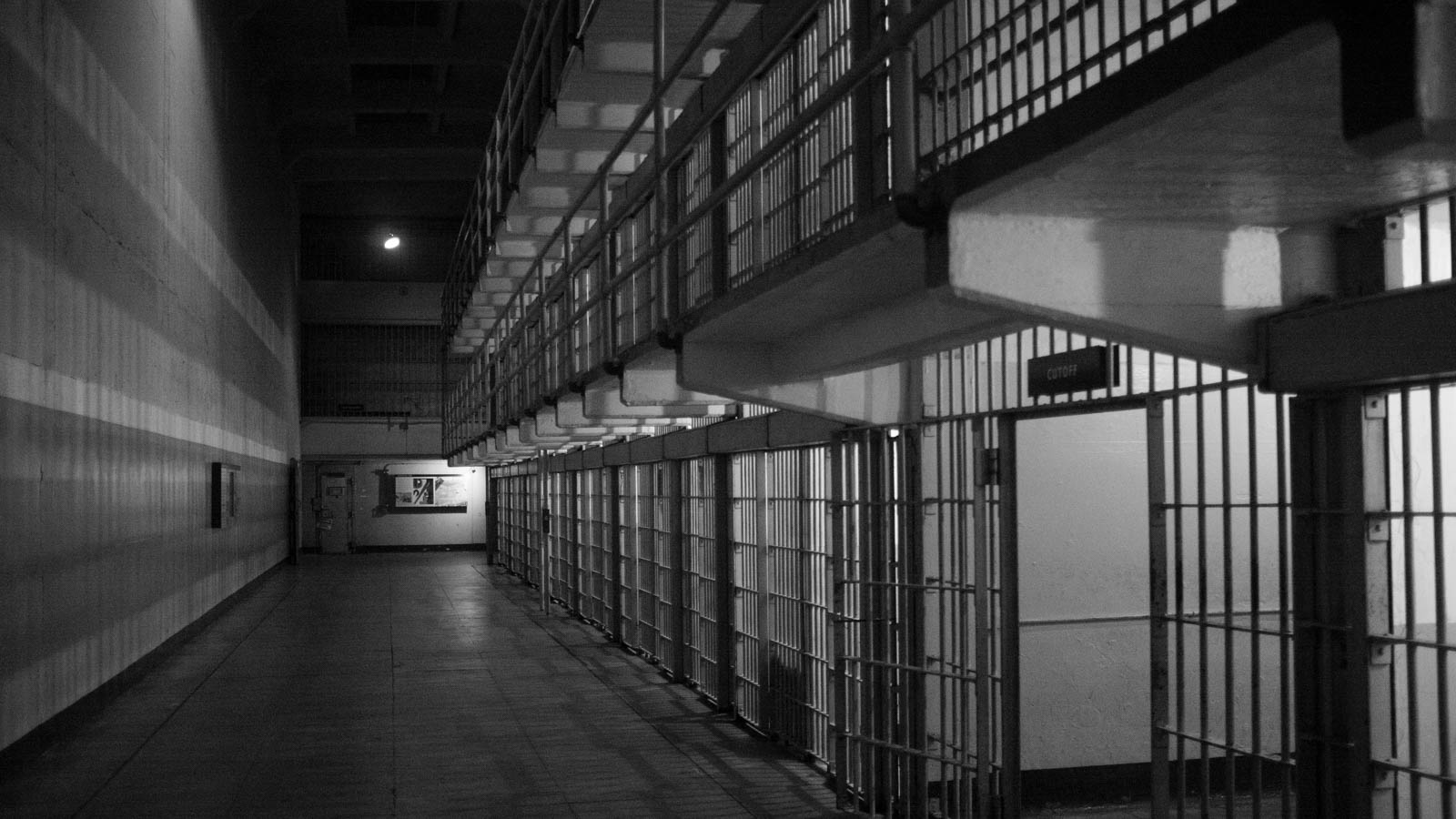

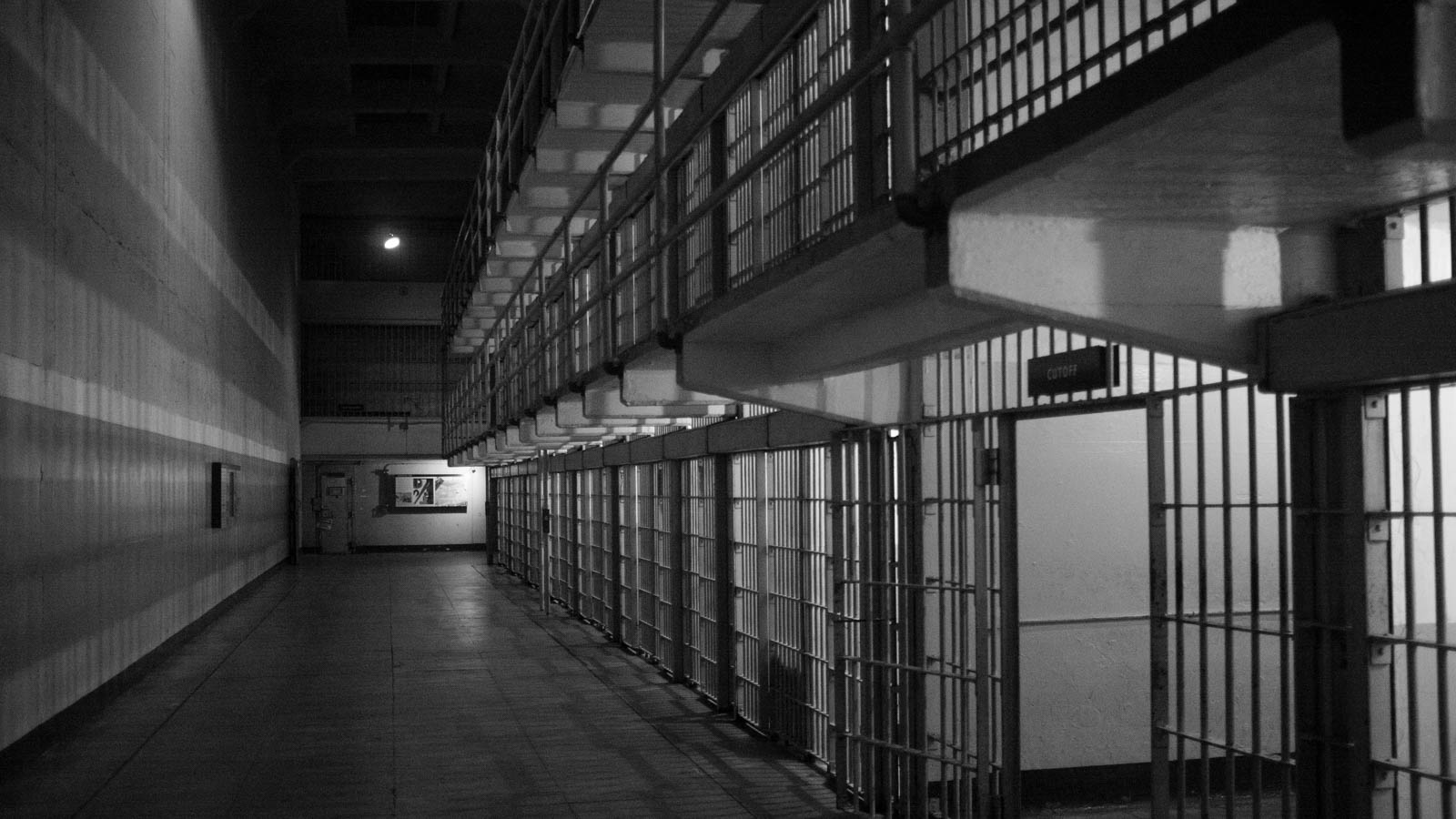

Having the law at his disposal, Anslinger was not shy about using it — and making sure the press heard how successful he was — starting with the first two arrests, made within hours of FDR putting his signature to paper. Samuel R. Caldwell, a 58-year-old unemployed laborer, sold a couple of joints to another unemployed laborer, Moses Baca, 26, in Denver. Both were sentenced to hard labor at Leavenworth Prison in Kansas; Caldwell for four years, Baca for 18 months.

Stories about Anslinger and the FBN sold newspapers. So, newspapers wrote more copy about him. But, there was a problem.

Reading his local papers, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, a hands-on politician known as “The Little Flower,” felt conflicted. The local papers described hideous crimes caused by marijuana smokers in his city yet he and his police department were oblivious. How could that be?

Fiorello Henry La Guardia (1882-1947) was Mayor of New York City (1934-1945). Here he’s pictured when he first served in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1917.

In “The Protectors,” his biography of Anslinger, John C. McWilliams wrote: “Personally skeptical that marijuana was capable of causing the bizarre behavior that had been attributed to smoking the drug, Mayor La Guardia was determined to organize an impartial, scientific, citywide investigation.”

Ironically, seven years earlier, La Guardia, then a member of the House of Representatives, had been a fan of Anslinger’s. According to McWilliams, La Guardia regarded Anslinger as a “most efficient commissioner who is building a real service of competent men.”

The committee La Guardia assembled included two internists, three psychiatrists, two pharmacologists, one public health expert, and the commissioners of Health, Hospitals, and Corrections, and the Director of the Division of Psychiatry. In addition, a Mayor’s committee made of physicians, chemists and sociologists conducted a two-part study that examined marijuana sociologically and from a clinical standpoint. McWilliams: “No aspect associated with marijuana smoking was ignored.”

The La Guardia committee’s findings debunked virtually every aspect of Anslinger’s marijuana mythology. In a nutshell: though marijuana was being used “extensively” (the report’s word) in Manhattan, it created feelings of “adequacy” in its users; it did not lead to addiction and did not serve as a “gateway drug.” Marijuana was not “the determining factor in the commission of major crimes.” School children were not using it. It did not lead to juvenile delinquency. And finally, “The publicity concerning the catastrophic effects of marihuana smoking in New York City is unfounded.”

The last finding may have been the one Anslinger objected to most. Booth noted: “No sooner was the report published than Anslinger waded into it.” Anslinger quickly wrote a book, “The Murderers: The Story of the Narcotics Gangs.” In Anslinger’s words, the report was “giddy sociology and medical mumbo-jumbo.” Booth again: Anslinger “labeled the authors dangerous men and started to rally the right-wing press, religious groups, and anyone else he could to his cause. He also destroyed all the copies of the report he could acquire.”

On the surface, as correct and true as it was, the La Guardia Committee Report accomplished little. But its ripple effects were huge. While Anslinger succeeded in burying the report in the U.S., the report did gain traction abroad. The United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs, on which Anslinger sat, sided with La Guardia’s findings. Made to look foolish, according to Booth, Anslinger continued his campaign against marijuana but, with a different focus. He went after musicians and other entertainers with renewed ferocity.

There was a second, far bigger ripple effect though. According to author Larry Sloman in Reefer Madness, A History of Marijuana,” this was the moment when Anslinger — ignoring the La Guardia Committee’s findings — manufactured a connection between marijuana and heroin. Riding the “gateway drug theory,” as bogus as it was, Anslinger had just sparked the skirmish that would, in time, metastasize into the war on drugs.

Next: The War On Drugs (Prelude)

Follow the “Blunt Truths” series:

- Introduction: How One Man Turned the Law and Society Against Weed

- Chapter 1: Harry Anslinger, the Prohibition Cop with Nothing to Prohibit

- Chapter 2: What Stoners Know that Harry Anslinger Didn’t Care to Know

- Chapter 3: Cannabis was Accepted Before Harry Anslinger

- Chapter 4: The Great Hemp Conspiracy

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6: All Publicity is Good Publicity

- Chapter 7: Harry Anslinger Goes Hollywood