May 22, 2020

NORML Founder Keith Stroup

For NORML’s 50th anniversary, every Friday we will be posting a blog from NORML’s Founder Keith Stroup as he reflects back on a lifetime as America’s foremost marijuana smoker and legalization advocate. This is the fourth in a series of blogs on the history of NORML and the legalization movement.

When we were initially pulling NORML together, we were all volunteers who had other jobs and were doing this on the side. But we knew the first most crucial challenge would be to identify sources of funding that would allow NORML to hire a professional staff. Perhaps it was a bit idealistic, or simply youthful naivety, but I recall thinking that if we put an effective program forward explaining what we were trying to accomplish, and why, somehow the value of what we were doing would be recognized by some of the progressive foundations who would step up and provide that funding.

And strangely, that is precisely what happened. (Sometimes luck is more important than skill!) Hugh Hefner and the Playboy Foundation ended up providing our initial funding in early 1971 and subsequently became our primary funder throughout the 1970s.

I had drafted a generic request for funding indicating what I envisioned for NORML and what our political goals were, and I had sent a version of this proposal off to a few progressive foundations, primarily those that were supporting anti-Vietnam war efforts. There was, even during these years, a stark cultural divide in the country between those who supported the Vietnam war and those who opposed it, and marijuana legalization had become a popular issue among the anti-war crowd.

I was receiving either no response, or nice notes saying they were sorry to disappoint, but that my project did not fall within their funding guidelines. I was beginning to think the concept of legalizing marijuana was simply too radical to get mainstream funding. Then, one day while visiting with one of the early Nader’s Raiders with whom I had become friends, John Esposito, he asked if I had sent a funding proposal to the Playboy Foundation. I had never even heard of the Foundation, but it made sense to me, and I did subsequently find the address in Chicago, where Playboy was then based, and where Hefner lived his public and lavish lifestyle at the then-famous Playboy Mansion. I sent off my proposal.

Within a few weeks I received a phone call from Margaret Standish, who served as executive director of the Playboy Foundation, asking for additional information, and suggesting we continue the discussion. Shortly thereafter I heard from Bob Gutwillig, a vice-president of Playboy, whom I had been advised was a personal friend of Hefner’s, asking if he could come visit me in Washington, DC. I met with Gutwilling, whose primary mission was to determine if I was a serious marijuana consumer advocate, or a radical political activist who might embarrass Hefner or Playboy.

Apparently, I passed the test. The next thing I knew I was invited to come to Chicago to meet with the foundation board, which was chaired by Hugh Hefner personally.

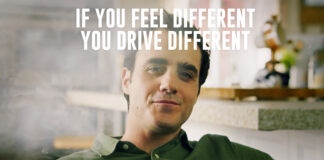

Hugh Hefner with “Dr. Hip” Eugene Schoenfeld and Keith Stroup during a NORML fundraiser at the Playboy Mansion in LA

That meeting, held at the Playboy Mansion where Hef both lived and maintained a complex of offices for a few of his key executives (he seldom went to the corporate headquarters, the Playboy Building, a few blocks away), was at noon. That, I was told, was early for Hefner to schedule any meeting, so it suggested he was interested in this one. That sounded promising, but it also intimidated me a bit.

I was slightly hung over, having gone out for drinks the night before with Burton Joseph, the legal counsel to the Playboy Foundation, and someone Hefner clearly relied on for advice in this area. It was at this time that I first met Bobbie Arnstein, a woman who would become a close friend and a valuable NORML ally.

Bobbie Arnstein was a beautiful lady from Chicago who had at one time been a lover of Hef’s, but who had since become his confidante and personal assistant, handling everything from his most important matters to his least significant matters. At some point Hef grew to depend on Bobbie so much that he asked her to move into her own apartment within the Playboy mansion, and she became a part of the family.

Bobbie was hip, in an urban sort of way. When I first met her, she ended up taking me back to her apartment in the mansion while we were waiting for Hefner, where she had, proudly positioned, as I entered her two-room black-walled pleasure palace, a copy of Be Here Now by Baba Ram Das, the former Professor Richard Albert from Harvard.

Bobbie was on top of the latest thinking on drugs and consciousness, and we ended up spending many evenings getting stoned and discussing our understanding of the universe. This woman was living the life most of us could only dream about. And she was, as it turns out, a real “head” who loved smoking marijuana, and a soul mate. We developed a special friendship that lasted until her death.

Hef was a couple of hours late for the Playboy Foundation meeting, not unusual for him, and the meeting waited for Hef. We all relaxed around the mansion, uncertain when Hef would come out of his private quarters.

Then suddenly he arrived, and Margaret Standish, the foundation executive director, called the meeting to order and immediately indicated the purpose of the meeting was primarily to meet me and to discuss the NORML proposal.

Broadcast journalist Nick Clooney, Keith Stroup and Hugh Hefner during a NORML fundraiser at the Playboy Mansion in LA on November 16, 1978

Bob Gutwillig gave a short summary of what he had learned with his site visit to DC, and it was generally favorable and positive. Margaret then introduced me and I made a short statement. I explained to them that I was a young lawyer, that I smoked marijuana, and I did not believe it should be a criminal offense. And that as I talked with more and more people, I found that they too felt this way. I stressed my experience working around consumer advocate Ralph Nader at the National Commission on Product Safety, and the fact that former US Attorney General Ramsey Clarke was working with us, because I knew that Hefner admired Ramsey. (I had asked Ramsey in advance if I could make that representation, and he assured me it was fine.)

I later learned that Ramsey Clark’s endorsement, underscored in a private communication between Clark and Hefner, would prove crucial in assuring our support by the Playboy Foundation.

Hefner, as best I can recall nearly five decades later, was upbeat and positive, asked a few general questions, but managed to keep his cards close to his chest. He made a couple of references about marijuana fitting right in with sex, but ended the meeting at some point with an assurance I would soon hear back from the foundation with a decision. He did not announce whether we would get support, or perhaps more importantly, what level that support might be.

I left the meeting feeling we would get the $20,000 I had requested in the initial grant proposal (a request that with hindsight seems relatively modest), and returned to DC. In a few days I received a call from Margaret Standish announcing they had voted to award NORML a $5,000 grant.

Initially I was uncertain whether to accept it or not. I needed to support my young family, and clearly $5,000 would not last long. Privately I was wondering what I would do when that initial grant ran out. Where would I find additional funding?

But after being reassured by Standish that additional funding would likely be forthcoming from Playboy, assuming they were satisfied with our work, I turned down a pending job offer, and began working full time on NORML, initially out of an office in the basement of my home in Dupont Circle.

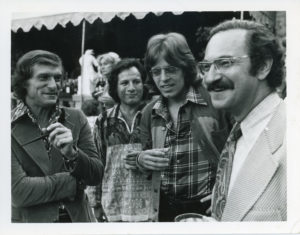

NORML ad in Playboy, 1977

By the end of the first year, the Playboy Foundation had come back with several modest supplemental grants, and then they seemed to find a plateau where they were comfortable, funding us at the level of $100,000 per year for the next 7 or 8 years. In addition, Playboy would provide us two full-page NORML ads in the magazine each year during those years, which allowed us to raise tens of thousands of donations from each ad and to begin to develop a membership base of supporters, whom we could use to lobby elected officials and to form state and local NORML groups. Playboy Magazine at the time had more than six million subscribers and a monthly readership that exceeded twenty million people.

And perhaps as important as was their financial support, Playboy magazine also began covering our work in flattering articles in The Forum, the news section near the front of the magazine. This prominent coverage introduced tens of millions of Americans to NORML and the work we were engaged in, which gave us almost instant credibility with the public and with elected officials.

Of course, there were times when I would have preferred to have as my principal financial supporter be an individual not quite as controversial as Hefner. Occasionally a state elected official would complain, or would refuse to sponsor a bill for us because of the Playboy connection. But far more common were those who knew about NORML and respected the work we were doing because they had read about us in Playboy magazine. Without question, there was baggage associated with the Playboy support, but it was a good and valuable tradeoff for NORML during the 1970s.

During one of my early visits with Ramsey Clark, when I was initially seeking to find funding for NORML, I asked Clark what he thought about NORML trying to get funding from the Playboy Foundation — whether he felt it undermined or otherwise cheapened our message by being associated with Playboy.

Ramsey, who by then had published several highly acclaimed books, including Crime In America in 1970, in which he called for marijuana legalization, said he had recently had his interview published in Playboy, and wherever he traveled, more people came up to him and asked him a question, or wanted to say hello, because they had read his interview in Playboy and recognized him, than from any other source. Now this is a man who only a couple of years earlier had been the attorney general of the United States and was now a major anti-war and civil-rights advocate. And he felt the ability to reach large numbers of individuals, many of them highly educated, through Playboy magazine was important enough that he could overlook the aspects of the magazine he did not really approve of.

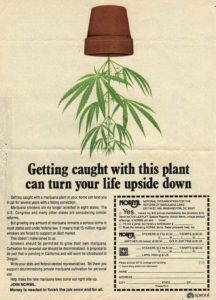

February 1977 Playboy interview of Keith Stroup

So I followed Ramsey Clark’s lead and was pleased to accept the Playboy Foundation money and enjoy their editorial support for the decade of the 70s. And because of Hefner’s personal support for NORML, I too was the subject of a Playboy interview in 1977, one of only a handful of non-celebrity interviews they have ever published. Hefner clearly wanted NORML to succeed.

While Playboy magazine and the lifestyle of the late founder and publisher Hugh Hefner seem dated today, post the ‘Me Too Movement,’ in the early 1970s Playboy was enjoying a well-earned reputation as an institution willing to challenge authority and prevailing sexual mores. Yes, the magazine featured nude models, but they also appeared to be fearless in celebrating hedonism and challenging the wisdom of criminalizing victimless crimes, including marijuana smoking. At the time they were working closely with ACLU and other groups concerned with protecting an individual’s right to privacy.

Like all men of my age, I grew up with Playboy magazine as a cultural phenomenon. Beginning in 1953 Hugh Hefner had created and served as publisher of the men’s magazine that celebrated sexuality and told us all that it was okay to enjoy sex without guilt. During my teenage years, it was the only magazine readily available that had pictures of beautiful, sexy nude women, and many of us were caught by our parents at one time or another with a copy of the magazine under our mattresses.

Most people think of Hugh Hefner and the Rat Pack generation he epitomized as more smoking jacket and scotch than tie-dye and pot, but the fact is that by 1970, Hefner had stopped drinking alcohol, and switched to drinking Pepsi Cola.

His drug of choice at this point was actually Dexedrine, or amphetamine – uppers. Hef, as he preferred that his friends call him, was working hard building an empire, and the use of amphetamines, the drug that helped many of us through our exams as undergraduates, permitted him to work for 24 or 36 hours in a row, when he was in a groove and did not want to stop. It was Hef’s favorite drug for a few years in the early and mid-1970s.

But he also enjoyed smoking marijuana, and he liked keeping a few pre-rolled joints in a container in his bedroom in the Playboy mansion. And it was my friend, Bobbie Arnstein, whose responsibility it was to keep that container refilled.

And occasionally whenever Bobbie would call me to say Hef was going to be taking a break from work, and this might be a good time to come hang out with them, I would fly to Chicago and stay in Bobbie’s apartment, waiting for Hefner to finish one of his marathon working jags and be ready to relax. Then Bobbie and I would play pinball with Hef for hours (he had more than 30 of the best machines ever made), until he finally got sleepy and decided to crash. During some of those pinball games we had hours to discuss NORML and how we were doing, and how we might do better. It was the most valuable time I ever had with Hefner.

Once, Bobbie arranged for me to come to Chicago to fly with Hefner on his famous black Playboy jet from Chicago to Los Angeles. When I arrived, Bobbie informed me that Warren Beatty and Shel Silverstein would also be on the flight. I was initially nervous, unsure I could hold my own in the conversation. I did my best to listen to their war stories (they really did start talking about all the women they had slept with during the flight!) and tried to keep quiet. Occasionally Hefner asked about NORML, so I didn’t feel totally left out of the discussion, but my role was miniscule. I had no war stories to contribute.

Bobbie Arnstein’s story ends tragically with her suicide, following a bogus federal drug trial and conviction, the result of her taking a trip to Florida with her boyfriend, a cocaine dealer. Hefner had paid her high-powered defense lawyer, and had made certain that she had the best possible defense money could buy. But that was not enough to save her.

On Jan 12, 1975, while she was awaiting sentencing, Bobbie checked herself into the Hotel Maryland just a couple of blocks from the Playboy mansion, where she took a lethal dose of prescription drugs.

Bobbie was a dear friend, and I felt a terrible sense of loss that I still feel today when I think about those years. She was a soul mate whose friendship was important to me and crucial to NORML.

Comedians David Steinberg and Flip Wilson with Hugh Hefner and NFL great Jim Brown at a NORML fundraiser at the Playboy Mansion in LA

The Playboy Foundation support for NORML continued through the end of the decade, and Hef even opened up his LA Playboy Mansion for a couple of high-ticket NORML fundraisers during the late 70s. But my ability to maintain a close relationship with Hefner was never the same after Bobbie’s passing. Following the brouhaha that arose regarding President Jimmy Carter’s drug adviser, Peter Bourne, using cocaine at a NORML party, I was forced to step aside from NORML for several years. That led to an end to the Playboy Foundation’s funding of NORML.

But they had made it possible for NORML to mount an effective reform effort during the 1970s. It’s fair to say that without the support of Hugh Hefner and the Playboy Foundation, NORML might never have advanced beyond the idea stage.