When Congress first made marijuana illegal in this country in 1937, most Americans knew nothing about it. At the time, marijuana use was associated primarily with migrant Mexican farm workers and black jazz musicians, two socially marginalized populations with little political leverage to effectively challenge the need for marijuana prohibition.

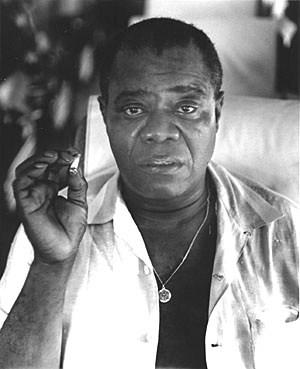

Louis Armstrong 1960

One such jazz musician was Louis Armstrong. Armstrong first began smoking marijuana in the 1920s and continued to do so throughout his entire life, including before his live performances and recording sessions. He was busted a couple of times, once in Los Angeles in 1930 when he spent nine days in jail for his “gage”, the slang term for marijuana in the jazz culture. But that only seemed to increase his commitment to smoking weed. In 1954 his wife Lucille was also busted in Hawaii with a couple of joints in her glasses case, which many observers assumed was really Satchmo’s weed.

Even though the threat of arrest and jail was very real for marijuana smokers during those years, and most especially for African Americans, Armstrong was devoted to his marijuana smoking nonetheless and he seemed to find a camaraderie among his fellow “vipers”, as the jazz culture called marijuana smokers. “That’s one reason why we appreciated pot, as y’all call it now,” he said. “The warmth it always brought forth from the other person – especially the ones that lit up a good stick of that ‘Shuzzit’ or gage, nice names.” He decribed marijuana as “a thousand times better than wiskey.”

Louis Armstrong’s importance to the legalization movement, in addition to being one of the earliest celebrity smokers, was that he, along with fellow musician Mezz Mezzro, who was Armstrong’s marijuana supplier for many years, is that he is reported to have first turned on Allen Ginsberg and the beat generation to marijuana. From the beat generation, marijuana smoking soon spread to the hippie movement and the anti-war movement of the 1960s, introducing millions of middle class Americans to this new experience. It was only when the middle class began to experiment with marijuana that we developed the access to political power to begin to change the system.

LeMar, the First Legalization Advocacy Group

The earliest marijuana legalization advocacy organization – at least the earliest of which I am aware – was a group founded in 1964 called LeMar (for Legalize Marijuana). It was started by beat poet Allen Ginsberg (who with Jack Kerouac and William Burrows formed the core of what became known as the “beat generation”), and later Fugs member Ed Sanders, (frequently credited with providing a bridge between the beat and hippie generations). LeMar was based in New York City’s Lower East Side and its members began to protest marijuana prohibition.

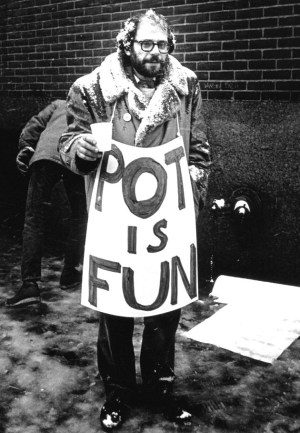

Allen Ginsberg at an early LeMar protest

On a cold day in January of 1965, Ginsberg and Sanders led a small pro-marijuana march outside the New York Women’s House of Detention where several left-wing war resisters were locked-up for civil disobedience. A small group of LeMar supporters chanted slogans and waved placards, resulting in a classic image of the 1960s – Allen Ginsberg holding a sign that read “POT IS FUN”. This was apparently the first of what would become regular “legalize marijuana” protest marches led by LeMar. None attracted large crowds during those early days, but their efforts started the process of gradually bringing marijuana smoking and marijuana smokers out of the closet, and making the case that there is nothing wrong with smoking pot. It is the crucial message that we continue to advance today, nearly six decades later.

LeMar Evolves Into Amorphia

During those years, Michael Aldrich, PhD., served as Allen Ginsberg’s personal assistant. His work with Ginsberg included legalization work with LeMar. Aldrich had founded the first college chapter of LeMar at SUNY-Buffalo in 1967, where he authored the first Ph.D dissertation on marijuana in the US entitled “Marijuana Myths and Folklore.”

In 1971, Aldrich and Ginsberg folded LeMar into a new west coast-based legalization group calling itself Amorphia. The new group also included Blair Newman, a west coast would-be entrepreneur; Gordon Brownell, a young lawyer who had been a Republican aide to Governor Ronald Reagan; and Todd Mikuyira, M.D., an Oakland, CA-based marijuana advocate who had previously conducted marijuana research for the US National Institute of Mental Health.

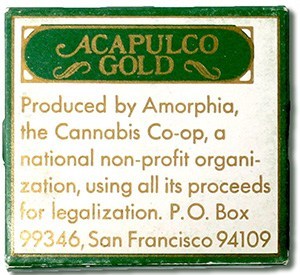

The genius of this effort, although it may have been an idea ahead of its time, was that Amorphia raised money to fund its legalization efforts by selling hemp-based marijuana rolling papers under the name of Acapulco Gold, a nod to what was then considered to be an exceptionally strong marijuana strain from Mexico. It seemed like perfect symmetry — consumers buy their papers from Amorphia, who in turn use that consumer support to legalize marijuana. The problem, however, was that rolling papers were considered to be drug paraphernalia if they were being marketed for use with marijuana. So retailers were constantly challenged to find creative ways to claim the papers were being sold only for use by those who still rolled their own tobacco cigarettes. For example, if a customer asked a store clerk if they had marijuana rolling papers, they were generally asked to leave the store. Otherwise the store risk being charged with selling “drug paraphernalia,” a criminal offense carrying the very real possibility of jail time.

When I learned of the existence of Amorphia, I was seriously concerned that NORML might not be able to financially compete with them. I was fearful that Amorphia might become the dominant marijuana smokers lobby and NORML might fade into oblivion, before we really had a chance to achieve anything substantive. But I did not want to acknowledge these insecurities, and I tried to talk a braver game.

And I’m sure the Amorphia folks were similarly concerned that NORML, with it’s Playboy Foundation funding and extensive coverage in the magazine, might manage to be the dominant marijuana smokers’ lobby. All of us realized that a direct competition for funding and political credibility was a risky strategy with no guaranteed winner, and with the possibility of dividing the legalization movement and weakening our ability to impact public policy.

Amorphia and NORML Open Merger Talks

When I initially met some of the Amorphia players (Michael Aldrich and Allen Ginsberg both testified at the same Marijuana Commission hearing in San Francisco in 1971 where I testified for NORML) we all played nice and said we hoped to cooperate and work on projects together. I even opened initial discussions with Amorphia about the possibility of merging the two groups (at that point, it was far from clear which name would survive a merger), and maximizing our reach and impact, and they were interested in pursuing those talks. To show good will on both sides, and to try to overcome the suspicion and distrust and competition that had already developed between the two groups, I invited Amorphia to send one of their people to live and work in Washington, DC, out of the NORML office, so we could begin to develop cooperative projects and see if we really wanted to move in the direction of a merger.

Amphoria Acapulco Gold rolling papers

So in 1971, only a few months after I had started NORML, Blair Neuman moved to Washington, DC and we began spending our days working together at the new NORML office I had recently rented a block away from my home, and spending much of our private time hanging out. Blair was an intense individual, clearly very bright and creative, but I was always a little uncomfortable when I was with him, not able to tell if his weirdness was just a result of his social awkwardness, or whether he might actually be a little crazy. Nonetheless, I recognized his genius in coming up with the idea of Amorphia, and going to Spain to establish the arrangement with rolling paper companies to begin producing the Acapulco Gold papers, so I wanted to find a way to work with him and his group.

Unfortunately, our relationship ended up being a casualty of the MDA period (a version of the party drug known today as MDMA or “Ecstasy”), when some of my friends and my (then) wife and I were experimenting with hallucinogens. My wife and Blair had ended up doing MDA one night when I was traveling (speaking to a college in the northeast), and when I returned the following day, they were just waking up from the long night, and it was clear they had enjoyed the sexual side of the MDA high. While I surely understood the tendency of MDA to lead to sex, I was not comfortable with the idea of an “open marriage”, as those relationships were called at the time, and I reacted by throwing Neuman out of my house, thus ending for the moment the efforts to merge Amorphia and NORML.

I not only sent Blair packing back to the west coast, I then moved out of the house myself and began living in the NORML office, ending that marriage. The townhouse had plumbing and showers and room for a bedroom, in addition to the work space, and it became my home for the next two years.

Needless, to say, the merger between Amorphia and NORML would have to wait another year. But, ultimately, it it was inevitable. In 1972 Amorphia was having trouble importing their Acapulco Gold hemp rolling papers which had interrupted their ability to raise revenue, and they were facing the real possibility of having to close their operations entirely. They were also having trouble getting some so-called “head-shops” to carry their brand of rolling papers because of the clear connection with marijuana, especially in the conservative states and the rural parts of the country, where marijuana legalization was still considered a highly contentious social issue. Already the staff had gone without salary for several weeks, and that was sufficient to rejuvenate the merger talks with NORML that had been sidetracked a year earlier.

Amorphia Becomes West Coast NORML

This time we quickly agreed that Amorphia would merge into NORML, with their political director Gordon Brownell, someone whom I respected and with whom I had become friends, assuming the role as the full-time west coast director of NORML, working out of the former Amorphia office in San Francisco and providing NORML with a far more visible presence on the west coast; and their business manager, Mark Heutlinger, moving back to Washington, DC to assume the role of business manager for NORML. There had been sufficient competitive bad-blood between the two groups that both sides were a bit suspicious of the other, and agreeing that Heutlinger could step into a position in which he would have full access to our financial records was an effort to be transparent. There would be no secrets from the former Amorphia folks; they could see for themselves that we were moving forward with the merger in good faith. In addition, we needed someone to help us manage the Washington operations in a more professional manner and Heutlinger provided us with some needed management skills.

I’m uncertain what happened to Blair Neuman, but the other Amorphia principals would remain active in the fight for legal marijuana. Dr. Tod Mikuriya would remain a major influence in the legalization movement in California, and later the medical use issue, where he was in constant trouble with the CA Medical Board for his willingness to recommend medical marijuana to anyone who wanted it, until his death in 2007.

And Michael Aldrich, the historian, would establish the Fitz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library in San Francisco, the largest collection of psychoactive drug books and related materials in the world, and later would play an active role helping those suffering from HIV/AIDS, running a medical marijuana dispensary for several years. Michael was awarded the NORML Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005. Today we are all proud of our merger with Amorphia and of the talent they brought to the early version of NORML.

Life usually makes more sense if one can follow the longer narrative and see the bigger picture, even as we struggle through the current political challenges. I have always felt emotionally and intellectually strengthened from understanding the direct linkage from those early legalization advocates and what we have accomplished at NORML . This is just the most recent chapter in the longer story of evolving marijuana policy in this country; first prohibiting marijuana based on ignorance, racism and “reefer madness” propaganda; and then starting the nearly six-decade struggle to correct that mistake and to end prohibition and legalize and regulate the marijuana market. That enormous challenge of reversing marijuana prohibition would not have been possible without the earlier work of LeMar, Amorphia and those pot-head jazz musicians and hip poets. We are all in this together.