NORML Founder Keith Stroup

For NORML’s 50th anniversary, every Friday we will be posting a blog from NORML’s Founder Keith Stroup as he reflects back on a lifetime as America’s foremost marijuana smoker and legalization advocate. This is the tenth in a series of blogs on the history of NORML and the legalization movement.

NORML appeared to be on an unstoppable legislative roll by the mid- to late 1970s. Legislatures in eleven states had enacted laws to stop the arrest of pot smokers, and with NORML enjoying a close relationship with the new Carter administration, we believed that even more significant progress was coming soon. After all, Jimmy Carter was the first US President ever to endorse the decriminalization of marijuana, first during his 1976 campaign and again in 1977 in a statement to Congress — which I helped to draft.

Helping Draft the President’s Statement to Congress Endorsing Decriminalization

I had become friends with Griffin Smith, a young staffer I’d met while lobbying the Texas legislature in 1973, and was pleasantly surprised to learn early in 1977 that he had been hired by the incoming President to be one of his White House speechwriters. Later that year, Griffin was assigned the task of drafting President Carter’s message calling on Congress to adopt the recommendations of the Marijuana Commission, and he (privately) invited me to his apartment to help him with it, which I was of course delighted to do. The draft we prepared was strong, and in his review of it Stuart Eisenstat, the president’s top domestic policy advisor, noted in the margins that the marijuana section “was written in an almost laudatory tone,” and that some of the draft appeared “to be a positive recommendation of the drug.”

“I support a change in law to end federal criminal penalties for possession of up to 1 ounce of Marijuana. Leaving the states free to adopt whatever laws they wish concerning Marijuana.” – Jimmy Carter (1977)

While President Carter did edit out some of our best lines, the speech, which Carter did send to Congress, was nonetheless the most pot-friendly statement any US chief executive has ever issued. Now it is important to acknowledge that decriminalization was likely supported by less than a dozen members of Congress at the time, and according to Gallup only by about 25% of the American public, so we were not close to actually decriminalizing marijuana under federal law. But it was, nonetheless, temporarily a high point for the movement.

At the time, we also benefited from the fact that for the first time Dr. Peter Bourne, the president’s drug policy advisor, was opposed to treating marijuana smokers as criminals and was someone with whom I had developed a good working relationship. Also important was the fact that I had by then also developed a personal relationship with Chip Carter, one of the President’s sons and a marijuana smoker himself.

It appeared the stage was set to kick the decriminalization movement into high gear, with the likelihood of adopting reform laws in many other states and under federal law over the next few years. But appearances can be deceiving, and the reality could hardly have proved more different. Within a matter of months, I had gotten myself mixed up in a political scandal involving President Carter’s drug advisor that would result in his resignation, an end to our working relationship with the Carter administration, and my resignation as the director of NORML.

Dr. Peter Bourne

Dr. Peter Bourne is a British-born psychiatrist and medical school graduate from Emory University in Atlanta, to which he had returned to teach just as Jimmy Carter became Governor of Georgia. Bourne’s innovative work with methadone as a means to get addicts off heroin caught the attention of Governor Carter, who began to rely on him to design innovative state drug programs, and the two became friends. In fact, Bourne once claimed he was the first person to suggest to Carter that he consider a run for the presidency.

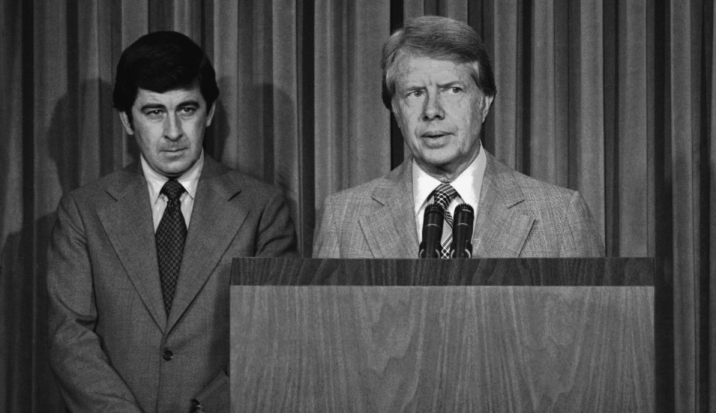

Dr. Peter Bourne and President Jimmy Carter. Photo: Bob Daugherty, AP

By the time Carter decided to do just that — a move met with skepticism by many, given that the Georgia governor was truly a Washington outsider and as such thought to have little chance of winning the Democratic nomination — Dr. Peter Bourne had become his acknowledged expert on drugs and drug policy.

In 1975 Bourne had been hired as a consultant by Dr. Tom Bryant of the Washington, DC-based Drug Abuse Council, which both brought Bourne to live in the nation’s capital and gave him the latitude to serve as candidate Carter’s main man in Washington during the early months of the campaign. It was then that I initially had the opportunity to meet and get to know Dr. Bourne, as I was also a consultant to the DAC. I found him to be a charming, likable man with a progressive approach to drug policy. He appeared to be honest and willing to challenge the traditional “lock-’em up” attitude shared by most so-called drug policy experts kicking around Washington, DC and offering their services to different candidates.

That same year, Dr. Bourne agreed to appear on a panel at the annual NORML conference in Washington, D.C, a bit of a political coup for a pot legalization group, and a sure sign that NORML would be coming in from the cold if Jimmy Carter were elected President.

Once Carter won in November 1976, he invited Dr. Bourne to serve in his administration as his special assistant on drug policy in the White House, a position the media would dub “Drug Czar” in later administrations. Regardless of the title, Bourne enjoyed both the trust and the ear of the President, a fact that delighted many of us as the new administration took office.

In early 1977 Dr. Bourne invited me to meet for lunch in the White House to discuss issues of common interest, particularly the recommendations of the 1972 Marijuana Commission and our mutual interests in seeing those recommendations implemented into federal policy. The meeting went well, and we agreed to stay in close contact and talk whenever there was a problem we needed to deal with.

But our relationship would soon begin to unravel over a number of minor policy disputes, and one not-so-minor policy dispute.

The Carter Administration Refuses to Allow Chip Carter to Testify for NORML

First, I had requested the President’s son, Chip Carter, to testify in support of the marijuana decriminalization bills pending in several states. It seemed like a perfectly rational proposition at the time, as candidate Carter had indicated his support for the Marijuana Commission’s recommendations during his campaign, and I knew that Chip himself smoked marijuana. But the idea was shot down by Jody Powell and Hamilton Jordan, Carter’s two most powerful political advisors, who had worked with him in Georgia and followed him to Washington, and into the White House.

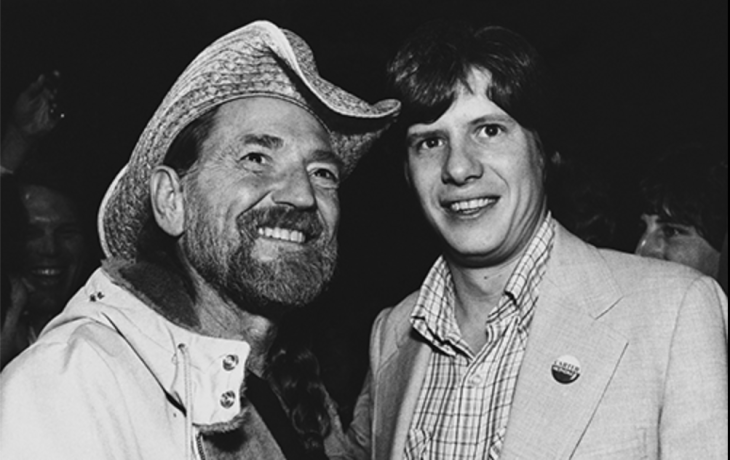

NORML Advisory Board Member Willie Nelson and Chip Carter

I was disappointed, as it seemed to me that if the new administration really supported decriminalization, as they claimed, they should be willing to expend a little political capital to work toward achieving this goal. Otherwise, their rhetoric sounded empty, and what was the point of electing a new President if his administration was unwilling to shake things up?

Looking back now with the benefit of hindsight, I realize it was way too early to give up on the new administration, but my attitude at the time reflected my total lack of experience working on the inside. From the moment NORML was established, we had been an aggressive pro-pot lobby that had no choice but to publicly attack the institutions of government, and whenever possible to lob rhetorical bombs at our opponents through the press. Those tactics had taken us this far, and I did not know how to switch gears, now that we had access to power.

In addition, I had witnessed others in Washington talk a strong game, then once they were hired as consultants or speechwriters or advisors to powerful politicians, became largely co-opted. I was determined not to let that happen to me.

And, I also have to acknowledge that I was an angry young man much of my life. Some of my resentment came from having grown up poor on a farm in Southern Illinois and seeing the advantages available to those with a more urban, upscale background. But regardless of my reasons, it is clear to me now that in the early years of NORML I was far too easily angered and far too quick to resort to tactics that would sometimes be effective in the short run, but were destructive to the process of building lasting alliances. By temperament, I was simply better suited to act as an outside agitator than to work on the inside.

The US Sprays Paraquat on Marijuana at the Mexican Border

But the more serious policy issue that would become the flashpoint early on between the Carter administration and NORML involved the US government policy of spraying the deadly herbicide paraquat on marijuana fields in Mexico. I had heard about this practice from several sources, including some friendly marijuana smugglers and our friends at the new pro-pot magazine, High Times, and that following the spraying, the fields had been harvested and the marijuana sold on the underground market. At the time, before the “grow America” movement had matured, an estimated 90% of the marijuana smoked in America came from Mexico, and we were alarmed that marijuana smokers in the US might soon be unknowingly ingesting the tainted pot, with potentially deadly consequences.

I raised this health concern with Dr. Bourne at our initial White House meeting, and Bourne first suggested that the herbicide was so effective that the marijuana would be destroyed. I shared with him the information I had regarding the harvesting of the marijuana following the spraying, and asked if he could at least find out if any of this tainted pot was coming into the US. The US had an ongoing program of testing marijuana confiscated at the US/Mexico border, so this should be a simple matter to determine. Bourne said he would check into the matter and report back, as obviously it was not their intention to poison American consumers.

In fact, there were some in the Carter administration, in the State Department and the DEA, who thought it was perfectly fine to poison marijuana smokers. “After all, it’s illegal,” was the position of the hardliners. But Bourne understood that just because marijuana smoking was illegal did not mean the government could knowingly poison those who defied the law and continued to smoke, any more than they could, for example, physically beat-up smokers or torture smokers. The Constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment would clearly render such a response illegal, and subject the government to potentially enormous civil liability.

When the testing results came back from the marijuana samples confiscated on the Mexican border, 13% of the samples were in fact contaminated with paraquat. And everyone, including the authors of a special report issued by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, conceded that smoking even a small amount of paraquat-tainted pot would cause permanent lung damage.

In response, NORML filed a major lawsuit against the federal government, seeking an injunction against the continued use of paraquat on marijuana fields in Mexico without first completing an environmental impact statement. But the federal judge dismissed the suit. NORML then looked to Congress to stop the spraying. Sen. Charles Percy was a progressive Republican senator from Illinois, and one of his key aides was Stuart Statler, one of my colleagues from the days at the National Commission on Product Safety. I had been keeping Statler apprised of our fight with the government over paraquat, and when our federal suit was dismissed, Statler and I came up with the strategy of having Sen. Percy introduce an amendment to the appropriations bill that would ban the government from spending any federal funds to spray paraquat on marijuana fields in Mexico. The measure enjoyed significant support, although Bourne and the Carter Administration were secretly lobbying against the measure.

And then a totally unexpected event occurred that brought the world crashing down around my feet.

First, in July of 1978, the Washington Post broke a front-page news story describing the arrest of a close aide to Dr. Bourne, a young woman named Ellen Metsky, for attempting to obtain some Quaaludes, a pharmaceutical tranquilizer then popular as a sexual stimulant, sort of Viagra before its time. Technically it could be prescribed for some legitimate reasons, but in fact most users were using it to enhance their sexual pleasure, and it was available from illicit market sources in singles bars all across America. That by itself would have been embarrassing to Dr. Bourne and the Carter administration, but what came next was the blockbuster: Peter Bourne had written the prescription for the Quaaludes for his healthy assistant, but to protect her privacy, he had written it in a fictitious name! Now the media really pounced..

While this Quaalude incident had nothing to do with NORML, it would shortly be connected by the media and brought to our front door. Or perhaps more precisely, to an upstairs room at a NORML party at a private home near Dupont Circle in Washington, DC that had occurred the previous December of 1977.

The NORML Party

NORML had established a tradition of hosting a big bash each year in DC, sometimes in conjunction with the annual NORML conference and sometimes as a stand-alone party. Initially these parties were held at my N Street house, and then at NORML’s M Street offices, but as the organization’s reputation had grown, a larger space was required. Two of my close friends at the time, Fred Moore and Bill Paley, Jr., who co-owned a couple of hip restaurants in town, offered to find a more suitable location, and came up with this lovely town house conveniently located in downtown DC.

We were expecting a few hundred people, and we had a band playing, a juggler and two or three bars serving alcohol. But the obvious factor was that marijuana was being smoked openly through the three-story townhouse, something new and daring for many Washingtonians. The District of Columbia had always been very button-down and traditional in terms of style and dress, and open marijuana smoking was well outside the limits permitted at most parties. One might get by going into a private room and sharing a joint, but you were expected to be discreet. After all, one inappropriate rumor circulating on Capitol Hill or around the other corridors of power could destroy a career or, at a minimum, cost someone their job.

But the NORML party was different. After all, we had by that time decriminalized marijuana in eleven states, we were constantly in the media talking about the need to stop treating smokers like criminals, and we had a significant presence on Capitol Hill, all based on the fact that we were the lobby for marijuana smokers in America. And we were not inclined to remain in the closet any longer. So I convinced a grower I knew from Virginia to donate a pound of dynamite marijuana for the event, and I had a couple of young volunteers spend the day of the party rolling hundreds of fat joints that we would freely distribute at the party.

The party in December of 1978 was a well-attended affair which included lots of Hill staffers and aides who would not generally be seen in such a risky atmosphere, but who were attracted by the cachet that NORML had achieved, along with our regular supporters who were only too happy to act as if marijuana were already legalized inside the townhouse on Dupont Circle. That was part of what attracted people to our events; they were more cutting edge than anything else in the city, more like something one might experience in Manhattan.

And then Peter Bourne arrived! Someone came running up to alert me that the President’s drug policy advisor was at the front door asking for me, where of course I was only too happy to greet him and to begin to take him around and introduce him to some of the cultural celebrities at the party.

Within a few minutes of arriving Bourne was being treated like a real celebrity – after all, the President’s drug advisor at a NORML pot party – that does indeed qualify as a celebrity appearance. We did not know in advance that Bourne was planning to attend, although we had heard one rumor to that effect. But until Bourne showed up at the front door, I had doubted the accuracy of the rumor.

Lots of people wanted to shake Bourne’s hand and thank him for his support for decriminalization. One of those, Jane Silver, a good friend of mine who worked at the Drug Abuse Council and who had known Bourne when he worked there previously as a consultant, came running up to whisper in my ear:

“Keith, Peter says he might enjoy doing a ‘line.’”

Clearly that should have set off alarms in my head, as cocaine, while quite popular at the time among the hip young set all across America, was still considered in a light far more serious than marijuana. To be busted with cocaine would still frequently bring a jail sentence, even for personal use. I should have simply said “I can’t help you with cocaine, but I can certainly arrange for a good joint.”

But I was feeling good, we had a houseful of Washington movers and shakers at our NORML pot party, and now the President’s drug advisor wanted to snort a line of cocaine and I wanted to keep him happy.

“That should not be a problem,” I said, since I knew several friends standing nearby were ‘holding’, as we used to say. “Let’s go upstairs for some privacy.”

So I walked over to a couple of people who I knew would enjoy being part of this scene, to let them know what was happening, and to invite them to join us.

“Bourne wants to do a ‘line,’” I said. “Can you help us make that happen?”

“Let’s do it,” was the instant response from my clearly surprised friends.

Then I led Dr. Bourne upstairs up an open two-story stairway that was visible to everyone on the first floor, to a private VIP room we had set aside for just such occasions, where Hunter Thompson; Christie Hefner; High Times correspondent Craig Copetas, David Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy’s son; John Walsh, then an editor at the Washington Post; and several other friends were hanging out and getting high.

That walk up the open stairs must have presented quite a sight to those who were partying on the first floor. The president’s drug czar and the head of NORML heading up to the VIP room. Just what would they be doing up there that required privacy?

As we arrived in the VIP room, I first introduced Peter Bourne to everyone, and then said, “Let me remind everyone that this event is private and strictly off the record,” intending the comments especially for the journalists who were present. I did not want one of the journalists to go home that evening and decide to break a major new story at our expense. By saying it was off the record, I wanted to establish that we were all playing by the same rules.

First, we all took turns passing around a few joints. I had several pre-rolled joints in my coat pocket, and I lit a couple and circulated them, as did several others. Very quickly some of those carrying cocaine started laying out lines on a mirror and passing the offering around with a straw until it reached Dr. Bourne, who snorted a couple of lines before passing the mirror on to the next person. He seemed to know the ritual, indicating he was not totally unfamiliar with cocaine and how it is used socially.

We continued this ritual for a few more minutes, when Dr. Bourne and I excused ourselves and headed back downstairs to mix with the larger group. After all, this was a Washington party, and it was important to meet and greet everyone who attended. Besides, by this time we were both obviously feeling quite high and enjoying ourselves, so it was no time to be hiding upstairs in the private room.

As we climbed back down the open stairway, and I could see many interested onlookers watching Bourne, I knew that most of them would presume what we were doing behind closed doors, and that this might have been a poor decision. But Peter had asked for the cocaine, and he was an adult, so I pushed aside my initial concerns and relished in the glow of the moment. Bourne stayed for a while longer, after which he said he needed to be getting home, excused himself and left.

There was some discussion among the attendees later questioning the wisdom of Dr. Bourne attending the party, and especially going upstairs with me, but nothing had happened to cause any problems, and we presumed we had ducked any bullet and no one would be hurt.

But now, several months later, the game was up. Once the journalists learned about Bourne writing the questionable prescription for Quaaludes to his assistant, a couple of them who had attended the party, one of whom was in the upstairs room with us, began to call to ask if they could write about Bourne’s use of cocaine at the December party.

When these calls first began to come in, right after the party, I used my friendship with those journalists to remind them the party was totally off the record, and to say they could not write about it. Initially, knowing I would not back them up, they really had little choice but to treat it as confidential. Their editors would never let them publish such a blockbuster and damaging story without at least one credible witness, and I would not play that role.

But as the months went by, and our fight with the Carter administration over paraquat spraying became more heated – “You are poisoning marijuana smokers,” was my frequent refrain in the media and in private meetings – I became less concerned about protecting Dr. Bourne. He appeared to be caving in to the advocates of spraying, even though I knew that he personally had no real enthusiasm for the program.

A Pie in the Face of a Panelist

The relationship became further strained when one of Bourne’s assistants, a gentle former law enforcement official and former consultant at the Drug Abuse Council, Wes Pomeroy, sent me a letter on White House stationery going on record as being horrified that I had been involved in a pieing incident at the last NORML conference.

I had made myself vulnerable to this type of criticism because of my appreciation for lefty politics, and especially what I saw as harmless street theater. I have always admired some of my contemporaries who have shown the courage to challenge the establishment in creative ways, even though I have myself generally tried to stay within more acceptable boundaries. At the time, I wore a coat and tie every day, for Christ’s sake.

The underlying incident was not terribly important, and involved Aaron Kaye, a Yippie activist who had made his reputation ridiculing his political targets, such as anti-gay activist Anita Bryant and a couple of New York politicians, by throwing a cream pie in their face at a public appearance. At our conference, Aaron had thrown a pie at Joe Nellis, an anti-marijuana zealot, legislative counsel to a House committee that handled drug policy, and had agreed to speak on a panel at the NORML conference. Nellis was an invited panelist, and clearly he did not anticipate when he accepted our invitation to speak, that he might be the target of a Yippie stunt, but he was, and he did not demonstrate much of a sense of humor.

That would have been bad enough, but those who were horrified by the stunt and thought it out of bounds soon learned that I had actually loaned a few bucks (for which he still owes me today) to Aaron Kaye to buy the pie, and I had suggested Joe Nellis as the appropriate target.

My only defense is that I enjoy some acts of civil disobedience, and throwing cream pies at people always seemed to me like a rather harmless way to make a political point, even if not one that I would generally recommend in the nation’s capitol.

When I subsequently confronted Dr. Bourne via phone about the matter, he claimed he was unaware of the letter (impossible, I’m sure), and agreed to send me a second letter thanking me for all my good work I had done. He did, but he sent it to me on his personal stationery, not the White House letterhead.

I had told Gary Cohn, a young aide to syndicated columnist Jack Anderson who had seen Bourne go upstairs at the party, and who knew what must have gone on, that if Bourne succeeded in getting me ousted from NORML, I would go on the record regarding his cocaine use at the party. Bourne and I both ended up backing off a bit, and although we continued to stay in touch on policy questions, neither of us ever fully trusted the other again. He had tried to get me fired, and I felt no loyalty to him.

Now Gary Cohn was calling, after learning of the Quaalude problem, asking if I would now go on the record about Bourne’s drug use at our December party. I was seriously angry at Bourne and the Carter administration for their refusal to stop spraying paraquat on marijuana fields in Mexico; I was disappointed at their failure to provide more support for our various decriminalization proposals pending around the country, and I was feeling no need to be loyal to Bourne. But I still realized that protecting Bourne was my only rational choice, both morally and professionally, and I refused Cohn’s request.

But later than night, when Cohn had written his column and just before it was to be distributed to the more than one thousand papers that carried Jack Anderson’s column, Gary called me at home, and in a serious tone told me that they were going to run with the story, even without my verifying what had occurred, but that he just wanted to make certain they were not destroying a man’s career by publishing a story that was incorrect. “Please,” he pleaded. “Just tell me if the story is accurate.” In a moment that I would soon live to regret, I told Cohen, “Off the record, it’s accurate.”

The following day, when besieged with calls from the Washington Post and most other major publications, I still thought I could avoid being a snitch by insisting on the line “I can neither confirm nor deny the story,” and that quote was widely carried all across the country, including on the front page of the Washington Post.

The phrase of “neither confirming or denying” is an old Washington phrase used by sources who want to drop a dime on an official, but who do not wish to be on record as having said anything incriminating. But only a total fool would have doubted the meaning of my response. I was no longer going to provide cover to Dr. Bourne. If he were unwilling to stop spraying paraquat or help us decriminalize marijuana across the country, he was on his own.

While I had not exactly snitched on Bourne, my failure to protect him was a violation of the basic principle that most marijuana smokers accept and live by, and that NORML had adopted as policy years earlier. It is never acceptable to rat on someone else, even if that would avoid a conviction or a jail term. The NORML Legal Committee had even adopted a policy during those early years that NORML lawyers should not represent anyone who wanted to get off by being a snitch – by testifying against another person. If they could not get smokers to testify against their supplier, it was often impossible for the government to work their way up the chain of commerce, and bust the big guys.

And regardless of how I tried to spin it, my failure to protect Bourne was the equivalent of dropping a dime on him. I knew when I gave that response to Cohn that the story of his drug use at the NORML party would run, and it would create a national scandal.

And it did. The next morning Jack Anderson broke the story on ABC’s “Good Morning America,” and all hell broke loose. At that point, I realized I would be persona non grata for the remainder of the Carter administration, and that many former friends on Capitol Hill would no longer feel comfortable working with me, and that so long as I was running NORML, the organization would be treated in political circles like a leper.

And, over the coming months, I concluded that I had overstayed my welcome and it was time to resign from my position as NORML’s Executive Director. I had created the organization from scratch and had literally spent the last ten years of my life totally immersed in its work and dedicated to achieving our political goals. But now I had, in one angry, frustrated moment, totally mishandled this incident, and brought it all tumbling down. Perhaps the organization could somehow right itself politically and continue on as the marijuana smokers’ lobby, but my role was finished. Or so it seemed at the time.

As I began to consider what I would do next to support myself, and my daughter, I felt totally lost. My entire identity for a decade had been wrapped up in NORML and my role as the chief spokesperson for legalizing marijuana in America. Now none of that would be possible, and it was truly a frightening prospect.

Little did I imagine that some 15 years later, in 1994, as part of a reorganization of the NORML board of directors, I would once again be invited back on the NORML board, and subsequently would be asked to serve another decade as executive director. Apparently there is sometimes a second act in American politics. That part of this saga did not seem possible at the end of 1978.