May 29, 2020

NORML Founder Keith Stroup

For NORML’s 50th anniversary, every Friday we will be posting a blog from NORML’s Founder Keith Stroup as he reflects back on a lifetime as America’s foremost marijuana smoker and legalization advocate. This is the fifth in a series of blogs on the history of NORML and the legalization movement.

Tom Forcade, Michael J. Kennedy and High Times Magazine

I first met Tom Forcade on the first day of the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida. At that time, I had no idea who he was, but I was about to find out. He and his creation – High Times Magazine — would become incredibly important to NORML and to the movement to legalize marijuana.

Tom Forcade (left) refuses to shake hands with Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman (right). Yippie Meyer Vishnu (center) tries to mediate an end to the Forcade-Meyer feud. 1971

The majority of dissident groups and anti-government protestors in Miami for the 1972 Democratic convention were bivouacked in Flamingo Park. which was re-dubbed The People’s Park by its many new residents. Forcade was there representing the Zippies (The Zeitgeist International Party), a splinter group he had recently organized as part of an internecine war going on between him and Abbie Hoffman’s Yippies (the Youth International Party). Tom and his fellow Zippies were selling ounces of marijuana out of a tree in People’s Park. I had no way of knowing at the time, but Tom and Abbie were in the midst of a bitter feud that began with a dispute over the publication rights to Hoffman’s Steal This Book. Their feud would ultimately end with Tom walking away from the spotlight of radical politics in favor of more discreet forms of social engineering.

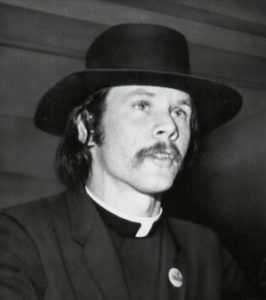

Rev. Tom Forcade

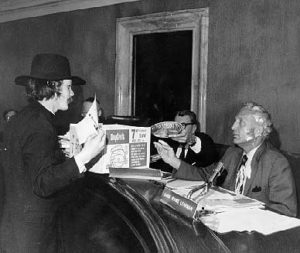

Forcade’s style of politics during his early political work was confrontational “street theater” and “in your face” tactics, literally. For example, appearing before the Senate Commission on Obscenity in 1970, the “Rev. Tom Forcade,” replete in black hat and a frock coat, denounced the “ancient myths of sterile blue laws” for several minutes in a stream-of-consciousness diatribe, finally concluding “So fuck off, and fuck censorship!” He punctuated his penultimate point by throwing a cream pie in the commissioner’s face while shouting his coda, “The only obscenity is censorship!” That was certainly not the only example of Tom showing his dislike or disapproval by “pieing” government officials; it was a favorite tactic, guaranteed to assure media coverage.

His real name was Gary Goodson, but back when he was a teenager in Arizona everyone called him Junior. Junior Goodson was a hotrod hell raiser who would regularly outrace the Utah State Highway Patrol just for fun in hundred-mile car chases on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Junior eventually turned his adolescent preoccupation with fast cars and adrenalin-fueled adventure into a successful career as a first-class marijuana smuggler. He changed his name to save his family embarrassment and quickly moved onto boats and planes as his mode of illicit expression.

Tom Forcade completes his testimony before the Commission on Obscenity by throwing a cream pie in the face of one of the commissioners

“There are only two kinds of pot dealers,” Tom Forcade used to say, “those that need fork lifts and those who don’t. I’m the kind who needs a fork lift.”

Tom was much more than an uncommon drug smuggler, however. He was a writer, an editor, a publisher, and a movie producer. He founded the Underground Press Syndicate which served as sort of the Associated Press for the media underground. It linked, in style and content, many of the geographically disparate counterculture magazines and newspapers that were popping up around the country. As always, Forcade was focused on ways to bolster the counter culture and to advance the progressive, anti-government agenda. Most important to Tom was the issue of legalizing marijuana.

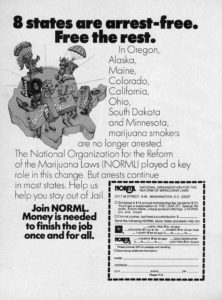

Little did I know that he would in a few years become a regular funder, sometimes personally and sometimes via his magazine. And, of course, High Times, the pro-pot magazine he founded in 1974, consistently covered NORML’s work and celebrated our accomplishments both editorially and in their news coverage for many decades. It is fair to say that during the 1970s, most Americans who knew about NORML had read about our work in either Playboy or High Times magazine.

The truth is that Tom Forcade, for whom the word visionary seemed tailor-made, accurately saw the potential of the legalization movement in Miami in 1972.

The People’s Pot Party brought cannabis politics to Flamingo Park during the 1972 GOP convention. Photo via State Archives of Florida

With so many protestors in Miami and so many progressive organizations trying to get their messages out, it was impossible for NORML or for any other social reform group to generate much media attention. The one exception, however, was the People’s Pot Party, another branding initiative by Tom, which was headquartered up off the ground inside an ancient eucalyptus tree near an entrance to Flamingo Park. If you wanted to score pot at the Miami Convention, you went to the eucalyptus tree in People’s Park, reached up with money in hand, and waited for a bag to float down from the leaves. It was the earliest version of a marijuana dispensary, and there was no age requirement or medical authorization required; just the courage to buy marijuana openly in front of hundreds of other protesters in the park. The People’s Pot Tree was audacious, illicit and, yeah, more than a little illegal. And the media ate it up. A picture of the eucalyptus tree even appeared in Newsweek.

“When I saw that huge crowd under the eucalyptus tree,” Tom later recalled, “I saw the politics of the 70s.”

Starting High Times Magazine

Following the 1972 Convention, Tom largely withdrew from the guerilla theater and media manipulation that characterized his earliest efforts and returned to marijuana smuggling with a fresh resolve. Forcade never retreated entirely from dissent, he simply shifted the direction of his protest. NORML became the primary focus of his financial contributions, and he let us take the front lines of the legalization movement while he increasingly withdrew to the shadows.

1975 NORML ad in High Times

Two years after our first meeting in Miami, Forcade put out the first issue of a national glossy magazine dedicated “to getting high… really high”. It was an instant success and doubled its circulation with each new issue until it sold almost a million copies a month. Tom Forcade did for marijuana what Hugh Hefner did for sex. He flouted his love of marijuana and getting high. High Times turned out to be his most enduring achievement and the publication of its first issue marked the beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship with NORML that lasted for decades.

In one of my favorite memories of Tom, I traveled to see him in New York City once when I really needed some cash to meet payroll or otherwise keep our heads above water at NORML. When I called him, Tom said, sure, he would help, but I would need to come to his place in the city. When I arrived, I was somewhat surprised to see the entire apartment filled from floor to ceiling with bales of marijuana. Tom and I did our business in the few feet available at the front of the apartment. He handed me a package with $10,000 in cash neatly wrapped, and I thanked him and left, just happy that no one had apparently noticed my brief visit, and we had not been busted. Tom clearly enjoyed pushing the limits, and watching his friends squirm.

Another time, in 1976, I called Tom to ask for a contribution and he said he would leave me a gift, but he wanted me to tell the press about the contribution, but claim it was from The Confederation, an alliance of marijuana growers and distributors. He hoped that by his example, other smugglers would step forward and help fund NORML. One Sunday morning he (or more likely one of his friends) left the cash in a black bag in front of the NORML office on M Street with a typed note indicating The Confederation was making the gift, rang the doorbell (where I lived above the office), and fled.

When I arrived, I brought the bag inside the office where I read the note and laughed out loud, since I knew it was from Forcade. Then, as promised, I called the Associate Press and the Washington Post and told them about this wonderful gift that had somehow mysteriously shown up at my door. And within hours an AP photo of the bag and the money, and a story about the gift appeared in newspapers all across America.

That was clearly a more innocent time, and Tom and I enjoyed pulling their chain a bit. Today one would likely be indicted under some fraud or money laundering statute, and the money would be forfeited to the government as the profits from a criminal enterprise. But the 70s were a more innocent time.

But over time Forcade began showing signs that his lifestyle and lack of discipline were starting to take their toll. He would frequently call the High Times office at all hours, stoned out of his mind on one drug or another, threatening to fire everyone; or on other occasions, promising bonuses to people whose work he thought was exceptional. The truth was that High Times had learned to get by with or without Forcade, as he would sometimes go on the road with one of the bands he liked for days on end, or disappear on another smuggling trip when he was similarly out of touch. He ran the magazine when he chose to, but he had put in place a team that published the magazine each month even when he was not in touch.

Forcade was a mercurial individual, a classic manic depressive, whose incredible flashes of brilliance were countered by severe bouts of gloom. He was also someone who wanted to personally experience all illicit drugs, including heroin, which he sometimes did when he went on the road with the Sex Pistols, a favorite band of his. And shortly before his death, Tom was also taking lots of Quaaludes, which can certainly cause depression. On November 16, 1978, on a complicated whim that resists dissection, Junior Goodson, a.k.a. Tom Forcade, in his New York apartment, put a pearl-handled .22 to his head and pulled the trigger. He was only 33 years old.

At a private memorial service held at the top of the World Trade Center, a few of Forcade’s friends, including the core staff at High Times and myself, celebrated his life by telling our favorite Tom Forcade stories and sharing a few joints, each of which contained a small amount of Tom’s ashes, and laughing and crying. Somehow smoking his ashes in a joint on the top floor of the highest building in New York seemed like an appropriate manner to honor Forcade’s extraordinary life. I am certain he would have approved.

High Times Following Forcade’s Death

Bill Rittenberg, Gerry Goldstein, Michael Stepanian, Michael J. Kennedy, and Keith Stroup at a Cannabis Cup event in Denver, CO

Forcade’s death had been a blow to all of us, if not a total surprise, and no one was certain initially if the magazine would even survive. But Forcade had assembled a good crew that kept the magazine coming out, including most importantly his long-time personal criminal attorney and High Times Legal Counsel (and chair of the High Times board of directors) Michael J. Kennedy. A nationally renowned, highly respected criminal defense and civil rights attorney, Kennedy was famous for representing some of the most radical anti-war activists and high-profile criminal and civil-rights cases in the second half of the 20th century. Kennedy’s clients over time included Chicago Eight co-defendant Rennie Davis, LSD guru Timothy Leary, Black Panther Party co-founder Huey Newton, Native American protesters at Wounded Knee, and anti-war activist Weathermen Bernardine Dohrn. He also represented other prominent Americans including Jean Harris, the private girl school headmistress charged with killing her lover, Scarsdale Diet doctor Herman Tarnower and in his only divorce case, he represented Ivana Trump in her divorce and property settlement with Donald Trump.

Hempilation I: Freedom is NORML

Kennedy remained in charge of the magazine until his death in January of 2016. During those years High Times always designated one of their senior editors as the “NORML person,” responsible for maintaining a cooperative and mutually beneficial relationship with NORML. During the early years when Forcade was still alive, that was A. Craig Copetas, a journalist who eventually left to become a writer based in Paris for such publications as Rolling Stone, the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News. Next, editor Steve Bloom became the “NORML guy” at the magazine, during which time he coordinated the production of two NORML benefit albums with Capricorn Records comprised of marijuana-related music, Hempilation I: Freedom is NORML, in 1995 and Hempilation 2: Free the Weed in 1997, raising more than $100,000 for the organization. Bloom eventually left to establish the marijuana news website CelebStoner, which he continues to run today. And more recently, associate publisher Rick Cusick was the designated NORML point person on the High Times staff until the magazine was sold and he and other staff were let go. Because of his close involvement with NORML over a number of years, Cusick was elected a member of the NORML board of directors in 2013, where he continues to serve today.

And during those decades following Forcade’s death, largely because of the support of Michael Kennedy, High Times became our largest source of funding, providing a free NORML ad in each issue, providing space each month for NORML to feature a leading grassroots activist from our NORML network around the country, and sending us a monthly check initially for $3,000 each month. These donations eventually increased to $5,000 each month and continued right up to the time the magazine was sold to a group of outside investors in 2017, when all funding to NORML stopped. These new investors were interested in monetizing the High Times brand and had no apparent interest in NORML or the marijuana legalization movement. For them, it was just another investment opportunity.

Eleanora Kennedy, widow of Michael Kennedy, speaks at the 2019 NORML Conference

Following Michael Kennedy’s death in 2016, NORML established an annual Michael J. Kennedy Social Justice Award to recognize those progressive individuals who are working to advance the cause of social justice in America.

Posted in : 2020, A Founder Looks at 50, ACTIVISM, Advocacy, Legalization