NORML Founder Keith Stroup

For NORML’s 50th anniversary, every Friday we will be posting a blog from NORML’s Founder Keith Stroup as he reflects back on a lifetime as America’s foremost marijuana smoker and legalization advocate. This is the twelfth in a series of blogs on the history of NORML and the legalization movement.

One can be tempted at times to dismiss the power that public protests possess to impact public policy. The hundreds of anti-prohibition protests that have been held in this country, starting as early as the mid-1960s, provide an interesting case in point.

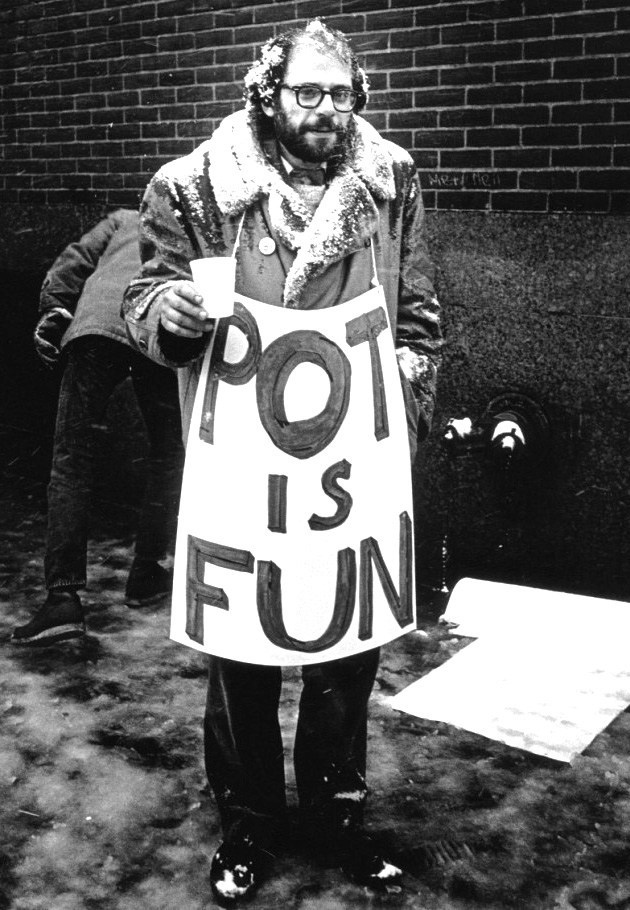

The early protests were primarily aimed to focus some media attention on the topic, even if the initial coverage was largely negative. Poet Allen Ginsberg wearing a sign saying “Pot Is Fun” in 1965, for example, was certainly not a serious attempt to change the marijuana prohibition laws — that was thought to be out of reach at the time (and it was). Instead, the protestors settled for changing the public’s perception of marijuana.

Allen Ginsberg at an early LeMar protest

Because marijuana was largely favored at that time by those on the margins of society, including countercultural “hippies” and many anti-Vietnam War protestors, frequently those early anti-prohibition protests looked more like Woodstock than a serious political event. And, for that reason, I’m sure they sometimes reinforced negative stereotypes among some of our political opponents.

But over time, those examples of people willing to stand up and challenge prohibition began to have an impact by gradually changing the public view of marijuana smoking and marijuana smokers. When concerned citizens are motivated to protest injustice in a peaceful manner, each protest brings us closer to acknowledging and addressing the injustice. The many marijuana protests represented an exercise of our First Amendment rights “of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Without those brave souls coming out of the closet when they did, we could never enjoy the level of public support we enjoy today.

The Free John Sinclair Rally

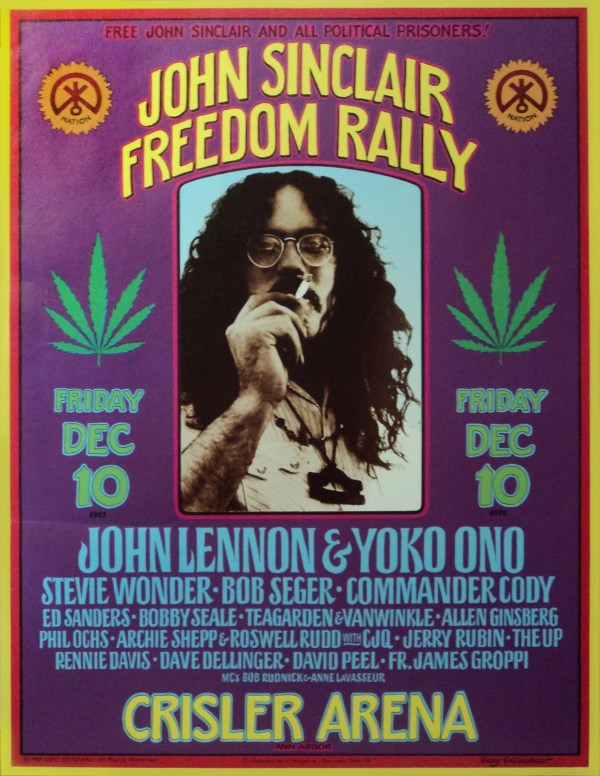

Early in the life of NORML, I was privileged to attend a protest against marijuana prohibition that was incredibly effective: the “Free John Sinclair“ rally (featuring John Lennon) held on December 10, 1971 in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

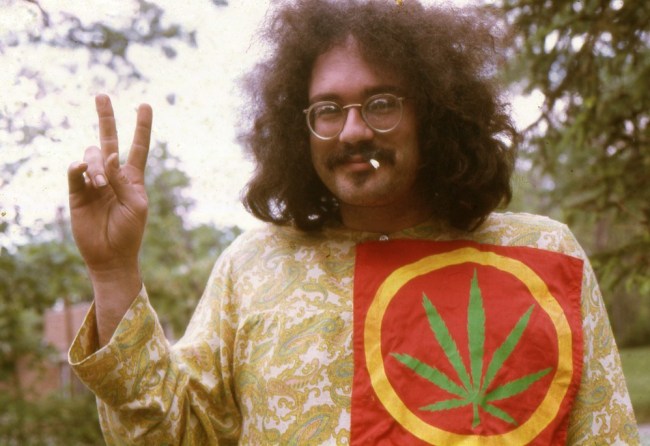

John Sinclair is a poet and radical political activist from Detroit who had helped found the White Panther Party, a militantly anti-racist countercultural group of socialists seeking to assist the Black Panthers during the civil rights movement. Following a couple of convictions for the possession of marijuana, Sinclair had been sentenced to 10 years in state prison in 1969 for giving two joints to an undercover narcotics agent.

John Sinclair in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1968. Photo: Leni Sinclair

His extraordinary sentence had caught the attention of other radical political activists, including Abbie Hoffman and fellow poet Allen Ginsberg, and most importantly John Lennon and Yoko Ono, who scheduled a “Free John Sinclair” concert and rally at the Crisler Arena in Ann Arbor, to draw attention to Sinclair’s plight.

Lennon, accompanied by Yoko Ono, David Peel, Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs and Bob Seeger, performed at the event, which also featured speeches by Allen Ginsberg, Abbie Hoffman, Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, Jerry Rubin and Bobby Seale, demanding Sinclair’s release from prison. It was a line-up comprised of the most radical anti-war and civil rights activists of the era, including several of the infamous Chicago Eight, who had been indicted and tried on inciting to riot charges following their anti-war protest at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Following an incredibly contentious federal trial, all eight had been acquitted.

I had heard about the event, and it just seemed so marijuana-centric that I felt it was something NORML should be part of, even if that meant simply sitting in the audience. The organization did not yet enjoy sufficient public recognition to get invited to speak, but knew we should be there. So, I drove from Washington, DC to Ann Arbor, purchased a ticket, and found my way to my seat, rather high up in the arena.

The first thing I recall noticing was that people were openly smoking marijuana throughout the arena. I had wondered if we would be allowed to smoke, or if the authorities, knowing the political purpose of the event, would send in undercover agents to bust anyone who dared light-up. And, being from out of town, I did not have a local source to obtain any weed, so I had arrived empty-handed.

It became quickly apparent that marijuana was effectively legal in Crisler Arena that evening. People were not only smoking joints openly and passing them around, but several people, including one sitting near my seat, had quantities of marijuana sitting open on their laps, freely rolling joint after joint, to make sure everyone who attended could get high for the occasion. It was the first time I recall ever seeing such mass civil disobedience, and it was empowering to experience. Tens of thousands of people openly smoking marijuana and no one being hassled by the police. Clearly someone had made the decision that it was better to allow these radicals to smoke at this event, than to attempt to arrest such a throng.

This was also the first time I had personally seen the Black Panthers in public, although I had previously seen them on the news, generally getting arrested for demanding greater rights for Black Americans in a manner that felt threatening for many white Americans. Before John Lennon took the stage, about 20 of the Black Panthers took their positions in a V-shaped formation, acting as body guards for Lennon and the band as they performed. I recall thinking it was one of the more intimidating scenes I had ever witnessed – a phalanx of big, tough-looking Black men, not a smile to be seen, appearing to dare anyone, friend or foe, to even think about approaching the stage.

Lennon obviously had thought something good might result from his focusing national attention on this unjust prison sentence for a minor marijuana offense, but I suspect he was as pleasantly shocked as the rest of us when, shortly following the event, the Michigan Supreme Court took action to free Sinclair.

Either it was an almost unbelievable coincidence, or the Michigan Supreme Court was listening to the message from the protest, because three days following the concert the court issued an order releasing Sinclair on bond, which had been previously denied by the lower courts; and on March 9, 1972 the court held the state’s marijuana laws were unconstitutional (cruel and unusual sentence; illegal entrapment; and misclassification of marijuana as a narcotic drug) and freed John Sinclair! The state legislature promptly enacted an anti-marijuana law that would pass constitutional muster, but for twenty-two days in 1972 there was no state law in Michigan criminalizing marijuana.

Telephone conversation between John & Leni Sinclair and John Lennon & Yoko Ono, December 15, 1971

Shortly after his release, Sinclair, whom I had been introduced to by mutual friends following his release from prison, and I, along with another marijuana cause célèbre of the early 1970s, Lee Otis Johnson from Texas, toured for several days in Arizona and Texas, speaking at college campuses and other friendly forums arranged by some NORML supporters who put up the money to cover our travel and hotel costs. Johnson, an African American student organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had received a 30-year prison sentence for giving a joint to an undercover agent before being freed by a federal judge after serving more than four years in prison.

And John Sinclair also attended the First People’s Pot conference, as we (foolishly) titled our first NORML conference, held at a church in Washington, DC in 1972. When one of the attendees was busted for openly drying a half-pound of marijuana on his car hood, John initially tried to organize a protest at the police station, before being convinced to let the lawyers deal with it. John refused to be intimated by the marijuana laws or by the threat of being re-arrested because of those laws.

I have remained friends with John Sinclair over these many years, most recently saw him at the 2019 Hash Bash in Ann Arbor, and still count him among the early heroes, and martyrs, of the marijuana legalization movement.

Appropriately, John Sinclair was the first person to purchase recreational marijuana when it became legal in Michigan on December 1, 2019.

John Sinclair makes the first adult-use cannabis purchase at Arbors Wellness in Ann Arbor on Dec. 1, 2019. Photo: MLive.com